Time is a return ticket in Ibrahim Mahama’s Songs About Roses, which is on display at the Fruitmarket Gallery, far and away the best show in this year’s Edinburgh art festival. Mahama draws young men lugging rails in detailed yet suggestively poetic charcoal, but are they laying tracks for the British empire’s Gold Coast railway – or removing them?

My attention was grabbed the moment I stuck my head through the gallery door. For this Ghanaian artist has produced a show as extraordinary as a great magic-realist novel on a theme such a novel might address: the rise and fall of the railway the British government built between 1898 and 1923 in its Gold Coast colony. It would win independence and become Ghana in 1957.

Defenders of the British empire’s legacy often point to railways as a positive achievement – but this one was built to move minerals and tropical wood for British profit, not for Africa. Mahama’s archaeology of this industrial behemoth shows in detail how companies back home in Britain profited. As well as his powerful drawings, in which African people struggle under the railway’s physical demands, there are painted replicas of Manchester engineering firms’ trademarks, films of decaying industrial spaces, graffiti painted on bark and photos of a performance-art reenactment of a rail being carried. The atmosphere he creates, of decay and futility, of a doomed colonial fantasy turned to rust, reaches its climax in the Fruitmarket’s Warehouse space, where you can still smell the engine oil in a loft reclaimed from an abandoned part of the city’s Waverley Station.

Here Mahama has built structures out of railway sleepers to display lifesized cutout portraits of former Gold Coast railway employees, drawn from formal group photographs. He has taken the little monochrome faces in stiffly posed pictures and made them live again as individuals. This reckoning with history’s ghosts puts Mahama up there with William Kentridge and Anselm Kiefer as one of today’s most important artists.

He also, nearly, makes sense of this art festival’s mission statement. For its 20th anniversary, it is “looking to artists, structures and figures who push back, and refuse”. I found it harder to see this matched elsewhere. Certainly not in a portrait of Winston Churchill at his easel in the south of France, one of the gentle paintings by the Belfast-born Sir John Lavery getting a sunny retrospective at the Royal Scottish Academy. I suppose Churchill, colonial secretary when Lavery depicted him, so actually responsible for the Gold Coast railway, resisted the end of empire. Lavery’s brushy, moist paintings of river scenes and the seaside are joyous by the standards of Victorian and Edwardian art, but I found the show slightly soporific, like a day at the beach with grandparents. He is certainly not an “Irish impressionist” as the show hyperbolically claims.

Defenders of the British empire’s legacy often point to railways as a positive achievement – but this one was built to move minerals and tropical wood for British profit, not for Africa. Mahama’s archaeology of this industrial behemoth shows in detail how companies back home in Britain profited. As well as his powerful drawings, in which African people struggle under the railway’s physical demands, there are painted replicas of Manchester engineering firms’ trademarks, films of decaying industrial spaces, graffiti painted on bark and photos of a performance-art reenactment of a rail being carried. The atmosphere he creates, of decay and futility, of a doomed colonial fantasy turned to rust, reaches its climax in the Fruitmarket’s Warehouse space, where you can still smell the engine oil in a loft reclaimed from an abandoned part of the city’s Waverley Station.

Here Mahama has built structures out of railway sleepers to display lifesized cutout portraits of former Gold Coast railway employees, drawn from formal group photographs. He has taken the little monochrome faces in stiffly posed pictures and made them live again as individuals. This reckoning with history’s ghosts puts Mahama up there with William Kentridge and Anselm Kiefer as one of today’s most important artists.

He also, nearly, makes sense of this art festival’s mission statement. For its 20th anniversary, it is “looking to artists, structures and figures who push back, and refuse”. I found it harder to see this matched elsewhere. Certainly not in a portrait of Winston Churchill at his easel in the south of France, one of the gentle paintings by the Belfast-born Sir John Lavery getting a sunny retrospective at the Royal Scottish Academy. I suppose Churchill, colonial secretary when Lavery depicted him, so actually responsible for the Gold Coast railway, resisted the end of empire. Lavery’s brushy, moist paintings of river scenes and the seaside are joyous by the standards of Victorian and Edwardian art, but I found the show slightly soporific, like a day at the beach with grandparents. He is certainly not an “Irish impressionist” as the show hyperbolically claims.

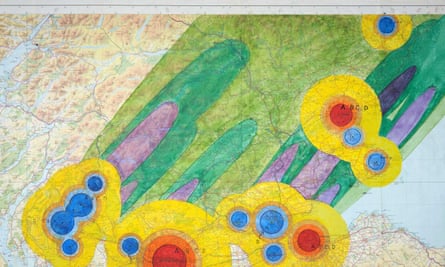

Lavery takes you into a lost historical world, and as I walked between the Old and New Towns trying to connect up the festival’s exhibitions, that sense of being lost in time recurred. Cold War Scotland at the National Museum is a display of relics from the 1950s to 1980s including steel blast doors from a bunker in East Kilbride. Stained by time and vandalism, they look like a Kieferesque artwork.

Source: The Guardian