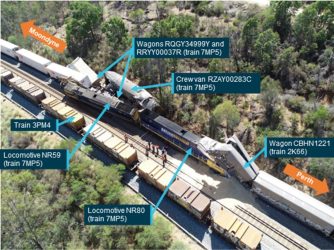

In the early morning of 24 December 2019, the driver of a Pacific National intermodal freight train was fatally injured when it collided with the rear of a stationary grain train at Jumperkine.

The freight train driver had passed a signal at caution, and a signal at danger – instructing them to stop – prior to the collision, but emergency braking was only applied when the grain train came into view.

“Despite being closely behind another train, the driver had passed 33 consecutive green signals over the two hours prior to reaching the signal at caution,” Chief Commissioner Angus Mitchell said.

“The driver was likely experiencing a level of fatigue known to adversely affect performance, and was almost certainly unaware they had passed the signal at caution, and then the signal at danger,” Chief Commissioner Angus Mitchell said.

The driver’s responses to the locomotive vigilance system timed alerts became slower as the journey progressed, but – consistent with the known limitations of these systems – it did not identify when the driver was fatigued and not attentive to rail signals.

“The ATSB concluded several fatigue-related factors, relevant to both individuals and organisations, either contributed to, or increased risk, in this accident.”

The driver’s fatigue was likely due to a combination of insufficient sleep in the 48 hours prior to the accident, and operating in the window of the circadian low, the investigation found.

“This accident highlights the consequences that can arise when train drivers perform their duties without sufficient sleep, and that the responsibility for managing fatigue in the rail sector is shared between drivers and operators,” said Mr Mitchell.

“Drivers have a responsibility to effectively use rostered breaks to rest, and self-report if they have had less sleep than required, and operators should promote an environment in which identification of fatigue concerns is encouraged, and any barriers to fatigue reporting are examined and understood.”

Since the accident, Pacific National has taken a range of safety actions to address issues with its fatigue assessment and reporting processes, as well as the limited controls available to manage the risk of signals being passed at danger during driver-only operations, including incidents associated with fatigue.

The investigation also noted that, like much of Australia’s freight rail network, the railway between Kalgoorlie and Perth lacks an automatic safety system to prevent a train from passing a signal at danger, or to stop a train which has passed such a signal.

This means the safeworking system is reliant on rail traffic crews observing and complying with displayed signal aspects.

“Although reliance on signal compliance has been central to the rail safety system in Australia for many years, it is fundamentally limited in situations where the driver is not fully attentive to the rail corridor or misperceives a signal,” Mr Mitchell said.

“Until automatic train protection or similar technology is considered viable, rail transport operators should ensure that the set of risk controls they have in place provides sufficient assurance to minimise the risk associated with signals passed at danger (SPADs) or other overruns of authority.

“The ATSB encourages rolling stock operators, industry bodies and others to develop technological improvements to vigilance systems or other technologies to enhance the ability to identify when drivers are fatigued or otherwise inattentive.”

Since the accident, the rail infrastructure manager, Arc Infrastructure, has also taken a number of safety actions, including amending its rules to require NCOs to make an emergency radio call to all rail traffic on the corridor when a train exceeds its limits of authority.

“Additionally, in response to this accident both Pacific National and Arc Infrastructure entered into enforceable voluntary undertakings with the Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator (ONRSR), prescribing a range of safety steps to be taken in response to the accident,” Mr Mitchell said.