At its most basic, a railway signal does not seem to be a particularly interesting subject. Put in the dry terms of the industry, signals are “safety appliances” that appear much like a highway traffic signal, intended to prevent collisions, and regulate the flow of trains. For railfans, though, signals are one of the most beloved parts of the North American railway scene.

Maybe this is due to their longevity. There have been signals for almost as long as there have been railways. Some of the earliest designs, dating to the 1850s, involved a painted ball that could be hoisted by rope up a pole for visibility from a distance. If you ever hear a conductor radio to his engineer the term “highball” as permission to proceed, this ancient signal is the likely origin of the phrase. Since then, signal technologies have evolved into a wide variety of designs spread across the main lines of the continent.

Signals are also long-lasting. Most railways in North America subscribe to the old saw, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” This means that older designs often persist for generations. Today, there are still signals in everyday use that were installed in the 1920s. What other technology lasts for a century?

For a railfan, signals hold a certain kind of promise. Even if a train is not present, a signal suggests the situation will change. In many cases, signals remain unlit or “dark” until a train nears, so when the lights come on (even if they are red) it means that there will be a train soon. This makes signals, intended to benefit railway employees, useful for the fan or photographer as well.

Then there’s the visual variety. Given how long signals have been around, and how much technology has changed over the last century and a half, there are many signal designs. Each has characteristics that are interesting — different shapes, patterns, lights, boards, and so forth. Some have lights set in round plates known as targets, some have valences known as hoods, and still others have moving arms known as blades. Almost all now have lit components, sometimes just a single light, sometimes three or five or more, sometimes in basic white or “clear,” sometimes in multiple colors.

Their physical arrangement varies as well, with some on short poles known as masts and some on tall ones, some mounted near the ground, and some arrayed across scaffolding “bridges” that span multiple tracks. While most are made from standardized parts, the number of possible combinations is made greater by the taste of each railroad.

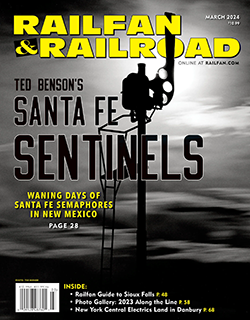

Signals do, however, fall to progress. While the semaphore was often the first choice for many railroads installing their first signal systems, these mechanical masterpieces were often replaced by some style of fixed lights. The main reason? Moving signals are more expensive to maintain. One of the last installations of semaphore signals outside of a museum can be found on the former Santa Fe line over Raton Pass.

Traversed only by Amtrak, the ancient semaphores are slowly being phased out, replaced with modern hardware. It’s one of the reasons photographer Ted Benson returned trackside to capture these iconic signals before their blades fall for the last time.

Still, time marches on, not just for semaphores. Old railway-specific designs are on the way out across the country. In their place are newer, more standardized designs, with fresh parts and manufacturer warranties. Practicality wins even as the aesthetic diversity of the landscape suffers.

Maybe it’s just nostalgia to long for those other signals — but isn’t it kind of strange that anyone ever longs for any mechanical device of the past? Devices made to save lives and improve cargo throughput are now viewed, by us in this hobby, as charming icons of times that we think, through the filter of memories or the stories of others, were somehow better. And yet, I find myself as susceptible as anyone.

—Alexander Benjamin Craghead is a transportation historian, photographer, artist, and author.

This article appeared in the March 2024 issue of Railfan & Railroad. Subscribe Today!

The post Before the Blades Fall appeared first on Railfan & Railroad Magazine.