by Otto M. Vondrak/photos as noted

They said it couldn’t be done. Two historic New York Central electric locomotives, trapped for more than three decades deep in the woods on private land near Albany, N.Y., without rail or road access, seemed doomed to a sad ending despite their historic nature. How they came to be saved is an amazing decades-long story of luck, determination, and perseverance.

New York Central embarked on one of the first large-scale applications of third-rail main line electrification, in part because of a deadly collision that took place in the smoke-filled Park Avenue Tunnel between two trains in 1902. A week after the crash, the railroad announced plans to electrify its suburban lines, which the state legislature solidified by passing a law prohibiting the operation of steam trains into Manhattan after July 1, 1908. While the initial plan was to simply electrify the short portion between Mott Haven Yard in the Bronx and the approaches to Grand Central, it was later decided to operate an “electric zone” 33 miles up the Hudson Division to Harmon, and 23 miles on the Harlem Division to White Plains, encompassing the suburban commuter districts of both lines and allowing for a change to steam power for through trains continuing north and west.

ABOVE: LEFT: NYC 100 and 278 pose outside the power plant in Glenmont on October 18, 1986. The equipment was moved here after an agreement to store the motors at the D&H Colonie Shops came to an end. —James Conroy photo, Kevin EuDaly collection

Building on their earlier success working with Baltimore & Ohio to electrify the Howard Street Tunnel in Baltimore in 1895, American Locomotive Company (Alco) and General Electric once again teamed up to design an electric locomotive for New York Central. The first prototype, No. 6000, began testing in October 1904. It quickly became clear the new locomotive had many advantages; the most obvious was rapid acceleration ideal for the closely spaced commuter stations. It was shorter and lighter than most steam engines then in use, and did not require a turntable because it could be operated in either direction from the center cab. Success of the new units is largely attributed to GE engineer Asa Batchelder, who obtained many patents for their revolutionary design. After extensive testing that concluded in July 1906, the new motors pulled their first train between Grand Central and Highbridge Station in the Bronx on September 30. An order was placed for 34 additional units, classed T-2 (with prototype 6000 the sole member of Class T-1).

The first scheduled electric service between Grand Central and Highbridge started December 12, 1906. Electric service on the Harlem Division between Grand Central and Wakefield started January 29, 1907. A deadly derailment in February led to the redesign of the motors to include two-axle leading and trailing trucks to help guide the heavy motors through curves. At this point, all 35 units were reclassed “S,” with an additional 12 Class S-3 motors ordered in 1908.

ABOVE: With redevelopment plans around the power plant property ramping up, DRM had to act quickly or loose the locomotives forever. On December 19, 2022, Hulcher successfully extracted the two historic locomotives and moved them 200 feet east to a staging area using four sideboom cranes. —Stan Matyda photo

Third rail was extended on the Hudson Division to Harmon (Croton-Harmon after 1963) by 1913, and to North White Plains on the Harlem Division in 1910, with another 30 miles north to Brewster added in 1984. A large part of the electrification project included the construction of the new Grand Central Terminal, opening in February 1913. The new terminal required a new class of heavier locomotive to cope with increased service. Also built by Alco-GE, the new Class T electric locomotives produced more power and were faster than the S-motors, with a top speed of 75 mph. In all, NYC ordered 36 new T-motors between 1913 and 1926.

The arrival of the T-motors heralded the downgrading of the S-motors to local trains and yard duty. As successful as they were, even the T-motors were eventually bumped from prime assignments with the arrival of rebuilt P-motors from NYC’s decommissioned electric zone around Cleveland Terminal in 1955.

Prototype S-motor 6000 was renumbered several times in its career; 3400 in 1906, 3200 in 1908, 1100 in 1917, and finally 100 in 1936. NYC 100 was retired and donated to the American Museum of Electricity in Niskayuna, N.Y., (near Schenectady) in 1966. It was later acquired by Mohawk & Hudson Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society in 1979.

ABOVE: The body of NYC 100 is carefully placed on cribbing on a 40-foot flatcar in the yard at Danbury Railway Museum on January 3, 2024. Once repairs are completed, it will be reunited with the chassis at a later date. —Otto M. Vondrak photo

Built in 1926, Class T-3a 1178 was renumbered 278 in 1936, and 4678 by Penn Central in 1968. It was acquired by Amtrak in 1971 and reassigned to work train service based in Sunnyside Yard in Queens, hauling the wire repair train (the tunnels entering Penn Station utilize third rail and catenary, so the T-motor could draw power from the third rail while the overhead wire was de-energized for maintenance). It was retired in 1980, and acquired by Mohawk & Hudson Chapter.

Both units were displayed at the Altamont Fairgrounds just west of Albany for many years, where volunteers had restored them to their mid-1950s appearance. Hollywood came calling in 1988, and the electrics briefly returned to home rails to film a few scenes inside Grand Central Terminal for box office bomb The House on Carroll Street. After filming, the units were returned to M&H, which unfortunately marked the beginning of their steady decline.

Upon return, the two electrics were moved inside a power plant located in Glenmont, N.Y., at the edge of the Port of Albany, because M&H owned no property of its own to store or display them. The plant was sold to Public Service Electric & Gas in 2000, which parked the electrics — along with an Alco RS-3, a GE U25B, and some other equipment also owned by the chapter — on an unused spur outside their gates. In 2003, the plant built a state-mandated wetlands remediation pond, and dumped the dirt from this project on the tracks leading back into the plant property. In 2010, a small bridge over the Normans Kill collapsed, which blocked any rail access to the equipment. In the meantime, nature began to take over the tracks, and vandals began to take their toll…

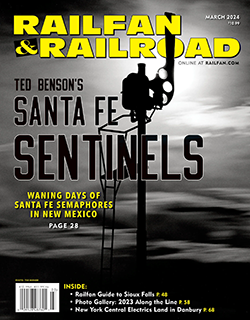

Read the rest of this article in the March 2024 issue of Railfan & Railroad. Subscribe Today!

The post Central Electrics Land in Danbury appeared first on Railfan & Railroad Magazine.