Railway enthusiast Brad Peadon is convinced time is running out to preserve remnants from the glory years of Australia’s cane trains.

Peadon, a railway historian with about 300,000 photos, many of them irreplaceable, is one of several ferroequinologists — a technical term for train buffs — struggling with failing health or fading memories.

Meanwhile natural disasters, weather exposure and shifting priorities continue to threaten bridges, tracks and locomotives that paved the way for sugar to flourish around the nation.

“There is, no doubt, some great work undertaken by a few museums,” Mr Peadon says.

“But for the most part you really wouldn’t have a clue of the extent cane train routes existed.”

As sugar mills face uncertain futures and governments monitor maintenance budgets, it is often retirees and volunteers left fighting for the cause, salvaging what they can.

While there’s a lot to preserve — about 4,000 kilometres of track, 250 locomotives and 52,000 cane bins still transport sugarcane around Australia — some valued mementos are already lost.

An enduring passion

Mr Peadon, 55, became fascinated with trains and trams when he was five.

“I used to ride the old railmotor from Robertson in the New South Wales Southern Highlands down to Wollongong with my grandparents on holidays, and that likely had a lot to do with it,” he says.

“My obsession with cane trains in particular traces back to the 1990s when I visited Queensland and saw a map of Nambour with a cane line running down the street.

“I found the line, the trains, then the old mill, which sparked an annual visit, where I would explore more and more.”

Among the friends Mr Peadon made was Clive Plater, now president of the Nambour and District Historical Museum.

Mr Plater’s great-grandfather was the first chairman of Nambour’s Moreton Mill, and father Edgar Plater served for 51 years as an engine driver, tramway and bridge supervisor, cane inspector and traffic operator.

Protecting the past

Mr Plater, who has written books about cane railways and received an Order of Australia Medal (OAM) for his services to community history, says sugar is what saw Nambour boom.

“The sugar mill was a great employer and a great thing for the town,” Mr Plater says.

“There were tractor dealers and car dealerships everywhere, and that’s what made the economy boom here for over 100 years.

“But there certainly isn’t much left and you can’t exactly blame the sugar companies or mill owners because they’re often obliged to pull up everything when a mill closes.”

Mr Plater and Mr Peadon agree one of the greatest difficulties in preserving cane railways is they are often on private land, running through farms.

They both rue the “tragic” failure to protect the old wooden Tramway Lift Bridge that spanned the Sunshine Coast’s Maroochy River.

Although a small section was removed in 2019 to be preserved at Nambour Museum, the rest was washed away by floods in 2022.

“As time went on, I knew they wouldn’t save the bridge because there was no maintenance done to it,” Mr Plater says.

“It was a picturesque spot, a nice spot to stand at, sail past, take photos or do a spot of fishing.”

In North Queensland, several other bridges used for sugar cane trains — which are smaller and have narrower wheelbases than regular trains — have been damaged or decommissioned in past decades.

When you add the loss of other tracks servicing bygone mining, logging and docking routes, for some railway enthusiasts it feels like history is being erased.

As recently as 2023, the head of the Light Railways Research Society of Australia warned the organisation may not exist past 2030.

Rise of the cane train

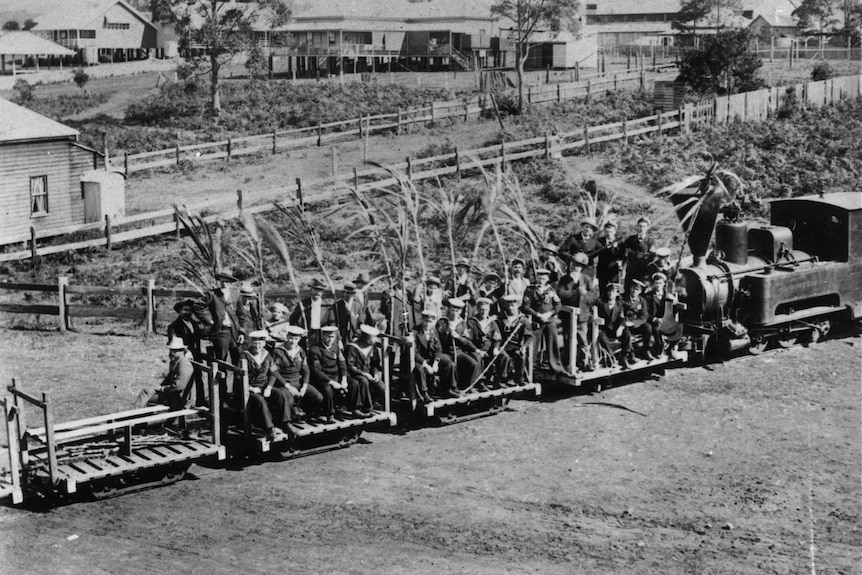

Trains became the dominant means of transporting sugar cane in Australia in 1882, although the defunct Morayfield Plantation (closed 1889), north of Brisbane, pioneered a traction locomotive in 1866.

Historian John Browning says prior to trains, sugar cane was first transported by wagons, bullocks and horses, then largely via waterways on a combination of vessels.

The locations along Australia’s eastern coast where sugar cane plantations flourished — places like Mackay, the Burdekin, the Tweed and northern New South Wales — commonly feature navigable riverways.

However, railways direct to mills were preferred by the end of the 19th century, reducing double-handling, losses of cane, and avoiding complex, shifting maritime conditions.

“The solution emerged with the development of light rail technology by the French sugar beet farmer and engineer Paul Decauville,” Mr Browning says.

Decauville worked with English firm John Fowler & Co to modify steam-powered ploughs used in agriculture, developing them into a patent for the Iron Carrier.

The Iron Carrier was the first iteration of what we now know as a cane train locomotive and was exported to places including Australia and Fiji.

Changes, both good and bad

Mr Browning, for one, doesn’t subscribe to a pessimistic outlook for cane trains.

“The truth is that they are flourishing and constantly adapting to enhance efficiency and effectiveness,” he says.

“Cane railways in Queensland are the envy of the sugar industry worldwide.

“They are by far the most economical and environmentally friendly method of cane transport.

“The investment by the sugar industry in cane railway networks has been significant.”

Despite this, more than 15 mills across Queensland alone have closed since the 1880s, including a raft since the dawn of the 21st century.

Nambour’s Moreton Mill (2003), Bundaberg’s Fairymead (2004), and North Queensland’s Mourilyan (2006), Pleystowe (2009) and Babinda (2011) mills have all shut down.

There has been constant speculation about the future of the Mossman Sugar Mill, which was placed into voluntary administration in 2023, but at the same time record prices have been recorded for sugar.

Who preserves what’s left?

Greg Shannon is a volunteer and board member at the Australian Sugar Heritage Centre at Mourilyan, just south of Innisfail.

Founded in 1974, the centre houses two vintage locomotives among other artefacts, but has been closed since the end of 2023 due to weather damage.

“We can’t get the power back on because the roof has leaked so bad. We don’t know if we’re going to reopen,” he says.

“We’re going to need about $400,000 and just don’t have the money.

“We’ve tried heaps of different forms of government funding, but it’s fallen flat, so now we’re chasing a couple of local businesses to see if they’ll get involved and help out.”

Like enthusiasts further south, Mr Shannon admits age and fatigue are starting to take their toll.

“There’s only been eight of us involved and the truth is we’re all getting tired,” he says.

One ray of light for narrow-gauge rail enthusiasts in 2024 has been the reopening of the Plantation Train circuit at Woombye’s Big Pineapple.

Ridden in 1983 by King Charles and the late Princess Diana, the modified cane train is popular with visitors of all ages.

As well as lovingly refurbishing the locomotive, Big Pineapple workers also replaced 700 sleepers and 250 metres of track previously damaged by vandals.

Time of the essence

When Brad Peadon suffered three strokes in August, his urging to preserve history gained additional perspective.

“I know the cost of maintaining infrastructure is immense, but we could have more interpretive signage around, denoting what was once there.

“One idea I liked was talk of illuminated representation of cane lines at particular points of interest,” he says.

“I’ve always felt the best history is from those who worked it, and I’d like to see more books and websites on the topic.

“Sadly, personal stories are often untold and, with each passing year, more and more are lost.”

ABC News Historical