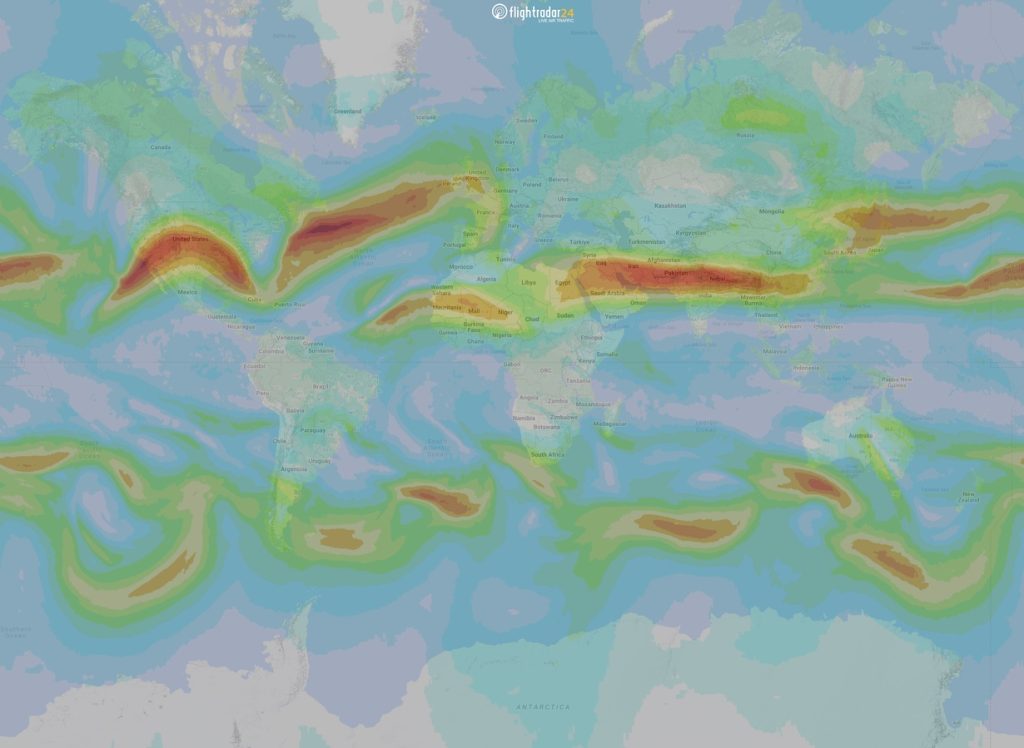

Let’s clear something up right from the beginning: none—not a single one—of the hundreds of commercial aircraft crossing the Atlantic Ocean in the photo above are traveling faster than than the speed of sound or “going supersonic.”

Now that we’ve got that out of the way, let’s get into what is happening and what it means for flights. Jet streams, illustrated on the Flightradar24 map by the color gradients, are stratospheric currents of air that swirl around the earth in the northern and southern hemisphere. Generally, there is a polar and subtropical jet stream in each hemisphere.

These “rivers” of fast moving air travel from west to east between roughly 30,000 and 40,000 feet and are especially beneficial to eastbound transatlantic flights during the winter months because of their position between North America and Europe. That has been the case this week as many flights have seen their flight times shortened considerably thanks to the strong jet stream.

How does the jet stream affect flights?

Jet streams affect only the ground speed of an aircraft, not the airspeed. The image above shows a Turkish Airlines flight traveling eastbound with the jet stream over Pakistan and a Hifly Malta aircraft traveling westbound into the wind. The ground speed difference between the two aircraft is more than 300 knots with the Turkish Airlines flight traveling 625 knots over the ground. But note that the Mach value for the Turkish Airlines flight is actually lower than Hifly Malta flight.

This is because Mach is the ratio of the speed of the aircraft to the speed of sound in the surrounding air. Commercial jet aircraft currently in service are designed to travel at 75-90 percent of the speed of sound at cruise altitude, or Mach 0.75 to Mach 0.9. Flying in a fast jet stream has absolutely no effect on the aircraft itself because the aircraft is still flying at the same speed relative to the air around it.

Getting there faster

If a near record setting jet stream doesn’t make an aircraft go supersonic, what good does it do? Well, if you’re flying with the jet stream, you’ll arrive at your destination faster. The fastest crossing from New York to London this week belongs to Virgin Atlantic flight 26 on 18 February. The 787-9 spent 5 hours, 46 minutes in the air with an average total speed of 520 knots and average cruise speed of 553 knots ground speed. The flight was 18 minutes shorter than the 30 day average.

The fastest crossing to mainland Europe this week is United Airlines flight 64 from Newark to Lisbon. The flight spent just 5 hours, 36 minutes in the air reaching a top ground speed of 727 knots thanks to the jet stream. But for the crew, this was just another flight cruising at the 787’s designed cruise speed of Mach 0.85.

Is faster always better?

For the eastbound day time flights a faster journey is undoubtedly a good thing, but for overnight flights a faster crossing can be a mixed bag. A faster crossing means fewer hours to sleep before having to deplane as there’s less time on board and the meal service on departure eats into more of your sleep time. There’s also air traffic control to contend with. Flights from North America that depart in the late afternoon are some of the first to arrive in Europe. With a strong jet stream, those flights can be left holding waiting for airports to open or for their landing time slot.

The post Fast, but not supersonic: what the jet stream means for flights appeared first on Flightradar24 Blog.