One of Western Australia’s oldest iron ore mines, and a chapter in its transformation into a global mining heavyweight, has officially closed with the final trainload carrying ore from the state’s Yilgarn region.

It follows the decision by Perth-based Mineral Resources in June to shutter its Yilgarn operations, with more than 600 of the 1,000-strong workforce redeployed and the rest either made redundant or resigning.

At the heart of the Yilgarn for decades has been the rich deposits at Koolyanobbing, about 430 kilometres east of Perth.

In the Indigenous Kaalamaya language of the Kaprun people, Koolyanobbing means the “place of large rocks”.

It perfectly describes WA’s Yilgarn, where iron ore has been mined on and off since the 1950s — the same decade the late Lang Hancock famously discovered rich deposits in the state’s Pilbara.

Mining and haulage operations finished at Koolyanobbing in early December and at other sites just before Christmas.

This week’s final iron ore train arrived at Esperance Port, on WA’s south coast, without fanfare ahead of shipment overseas.

While the last trainload marks the end of an era, there are hopes Mr Hancock’s daughter, Gina Rinehart, could eventually revive iron ore mining in the Yilgarn on an even bigger scale.

The early pioneers

Kalgoorlie prospector Lindsay Stockdale spent decades as a builder before retiring in 1990 to spend more time in the bush searching for gold.

It was that same pioneering spirit that saw the apprentice carpenter living in a tent in 1965 while working on the construction of a new mining town called Koolyanobbing.

“There was nothing there in those days … just bush,” the 79-year-old said.

Mr Stockdale’s brief stint at Koolyanobbing involved building the local school in a community where the population peaked at nearly 500 in the early 1980s.

The town site, which emerged out of the bush landscape, also included a swimming pool, general store, golf club, bowling green, and town hall.

“To be down there at that early stage, it felt like you were a pioneer,” he said.

“Driving an FJ Holden ute, a two-wheel drive into those bloody hills and then getting out with hand tools and mixing concrete by hand … it was hard work but I loved it.”

Curtain call for mine

Before WA’s Pilbara region became the economic powerhouse it is today, it was iron ore from the Yilgarn that helped shape the state’s future prosperity.

That reliance on the steel-making ingredient has the WA government forecast to collect $903 million in iron ore royalties this financial year alone.

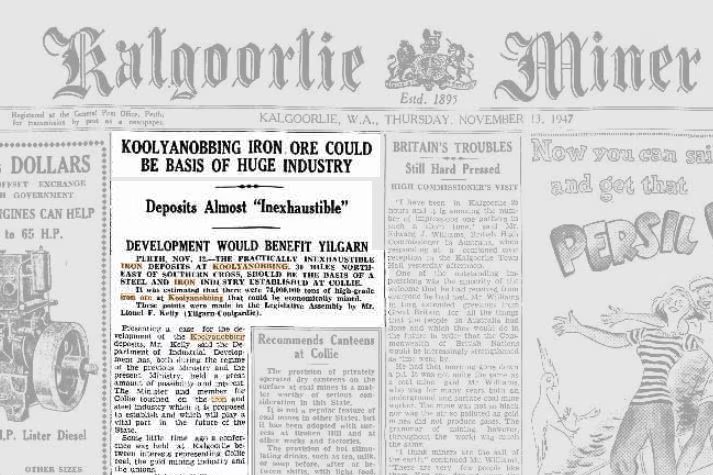

But the industry was virtually non-existent in the 1940s when prospectors pegged out the ground and newspapers wrote about the “practically inexhaustible iron deposits” at Koolyanobbing.

Nothing lasts forever and Koolyanobbing is once again transitioning from an operating mine into a virtual ghost town.

Just 45 workers will remain for care and maintenance activities.

Rich history in Yilgarn

Pioneering prospector Henry Dowd is credited with the discovery of iron ore deposits at Koolyanobbing in the 1890s.

But he believed the rocks did not hold much value, placing a transcript of his findings in a bottle and burying it on a hill at the foot of a surveying peg.

The area, later known as Dowd Hill, would become one of the main deposits at Koolyanobbing with about 60 million tonnes of iron ore.

In 1960, the WA government and mining giant BHP reached an agreement on the establishment of an integrated iron and steel works at Kwinana, south of Perth.

But it was contingent on the construction of a standard gauge railway link for Koolyanobbing.

It took 2,000 men six years to build the line.

“It was iron ore at Koolyanobbing — required for a steel industry at Kwinana — that made it necessary to build a standard gauge railway,” premier David Brand said in February 1966 at the opening of the Perth to Northam line.

“But it is equally true that rail transport — in the form of standard gauge — made the steel industry an economic proposition by bringing iron ore transport costs within reason.”

City of Kalgoorlie-Boulder historian Tim Moore said the standard gauge line led to the introduction of Australia’s transcontinental train, the Indian Pacific, which has run continuously from Sydney to Perth since 1970.

“Koolyanobbing is closer to Perth than the Pilbara, so it was a big pork barrel that we build a rail line to transport the iron ore to Kwinana,” he said.

“The flow-on effect was the Indian Pacific could go all the way from Perth to Sydney, so it was a boon for the state, shifting freight and people from coast to coast.”

Changing fortunes

The so-called Big Australian, BHP, created a new subsidiary in 1965, the Dampier Mining Company, to operate Koolyanobbing.

The first trainload carrying 1,500 tonnes of iron ore from Koolyanobbing rolled into Kwinana to feed the blast furnace in April 1967.

By 1970, five ore trains a week were running between Koolyanobbing and Kwinana.

But there was trouble on the horizon.

The world steel industry entered a downturn in the early 1980s, resulting in BHP shutting down operations at Kwinana and Koolyanobbing.

During the early 1990s, mining at Koolyanobbing was restarted by Perth-based company Portman.

It had a much smaller workforce and transported ore by rail to Esperance, about 580km to the south.

In 2008, Portman was taken over by US miner Cleveland Cliffs, which operated Koolyanobbing for a decade.

Its decision to close Koolyanobbing in 2018 prompted the state government and current owner Mineral Resources to broker an 11th-hour deal, which included a five-year royalty holiday worth about $270 million.

The Chris Ellison-run company argues it was money well spent, saying it had exported almost 45 million tonnes of iron ore and spent $4.2 billion in the Yilgarn since 2018.

But those numbers were starting to dwindle with just 7.6 million tonnes of Yilgarn iron ore shipped via Esperance last financial year.

That number pales in comparison to the world’s largest bulk export port, Port Hedland in the Pilbara, which exported 564 million tonnes of iron ore in the same period.

What’s next for Yilgarn and Esperance?

Since the closure announcement, Mineral Resources has redeployed more than 600 workers, mostly to its $3 billion Onslow Iron project in the Pilbara.

The company has said all future options are on the table for its Yilgarn assets, including rehabilitation or disposal.

The closure is set to impact Esperance Port, which was also hit in 2024 by the closure of the Ravensthorpe nickel mine and the Bald Hill lithium mine.

Another port customer is the Mt Cattlin lithium mine, scheduled for closure in mid-2025.

A small part of the void is being filled by Perth-based miner Gold Valley, which has shipped nearly 250,000 tonnes of iron ore from its Wiluna West mine, in the northern Goldfields, since October.

The iron ore is being trucked to Kalgoorlie-Boulder and then sent by rail to Esperance, a journey of about 900km.

“Our Port of Esperance iron ore circuit was not originally designed to be shared by multiple customers,” Southern Ports chief executive Keith Wilks said.

“Now that we have shown it can be agile and work this way, it presents new opportunities for how we can work with prospective customers in the future.”

The emergence of Gina Rinehart as a major backer of a new magnetite project in the northern Goldfields has also provided some renewed hope for future development in the region.

Her company, Hancock Prospecting, committed another $20 million in September to the development of the Mt Bevan project, about 100km west of Leonora, which has a direct rail link to Esperance Port.

A likely investment decision still appears years away and despite Ms Rinehart’s deep pockets, early estimates suggest it would cost at least $5 billion to bring into production.

But it is something Australia’s richest person has done before, at Roy Hill in the Pilbara, and raises the possibility that more mining investment could yet make its way to the region.