By Adam Estes

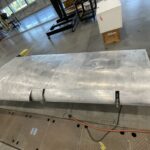

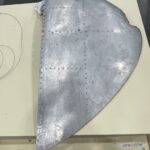

On a typical day at the National Air and Space Museum (NASM)’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, thousands of visitors look down from the glass mezzanine of the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar to see specialists putting their centuries of combined experience to work on the restoration and conservation of some of the most historic aircraft and spacecraft in the world. With the ongoing renovations at the National Mall building in the heart of Washington, D.C., many of these collections are being prepared for their arrival at some of the new galleries that have yet to open.

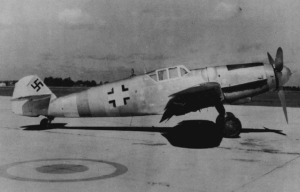

Among the aircraft being readied for the return to Washington, D.C., is a Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6, an example of the most widely produced fighter aircraft of the Second World War. Yet this Bf 109 once kept a secret for fifty years, one that was revealed some thirty years ago now—a remarkable story of one man’s dash for freedom during WWII.

In 1972, construction began on the National Air and Space Museum’s first permanent building on the National Mall after nearly 20 years of design studies. The goal was to open the building for the upcoming Bicentennial celebrations in July of 1976.

Meanwhile, restoration specialists at the Silver Hill Storage Facility (later the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility) in Suitland, Maryland, began preparing designated aircraft for display at the new museum. Among them was the Bf 109. The aircraft had been virtually untouched since the end of WWII, but with a missing main data plate and no records on file about its exact history before arriving in the USA and an approaching deadline for being sent to Washington, specialists and curators decided to paint it in the markings of Bf 109 G-6 Werknummer 160163 “White 2,” which was assigned to the 7th Staffel (squadron), 3rd Gruppe (group) of Jagdgeschwader 27 (JG 27) and based on several wartime photos that were available to the team. Additionally, new research into Luftwaffe paint and stencil schemes would be employed to create one of the most accurate restorations of a German WWII aircraft for the time.

In April of 1974, the 109’s restoration was complete, and by the time of the opening ceremony presided by President Gerald Ford on July 1, 1976, it was sharing the WWII gallery with a P-51 Mustang, Macchi C.202 Folgore, Mitsubishi A6M Zero, Supermarine Spitfire, and the nose section of the Martin B-26 Marauder known as “Flak-Bait,” which flew more missions than any other American bomber of the war.

Yet there was still the mystery of the Messrschmitt’s exact identity. As early as 1976, author and researcher Thomas H. Hitchcock, who had gained unprecedented access to the aircraft during the research for the sixth installment of Monogram’s Close-Up book series, came to believe that the NASM aircraft may be the same one that had landed in Santa Maria Capua Vetere, near Naples, Italy, on July 25, 1944, based on some details noted in wartime documents and photographs that suggested that there were details found on both the 109 at Santa Maria and the Smithsonian’s example … from the combination of its long radio mast and Peilrahmen PR 16 radio loop antenna mounted just behind the cockpit to the ragged edges of the shell ejection chutes for the nose-mounted MG 131 machine guns lining up perfectly with the reference photos from Santa Maria. However, Hitchcock was unable to irrefutably prove that the two aircraft were the same, but it was a lead for others to go on.

12 years later, in 1988, British researcher Nick Beale uncovered Allied reports of a Bf 109 G-6, Werknummer 160756, that had been flown to Allied-occupied Italy in July 1944 by a deserting pilot. The report highlighted some of the same details that Hitchcock had noted previously as correlating to the Smithsonian’s example. Beale informed the museum of his suspicions and in October of 1989, future curator Tom Dietz made a thorough inspection of the Messerschmitt. Behind the cockpit armor plating, he found a data plate that had been painted over during the 1972-1974 restoration that confirmed that the aircraft was Werknummer 160756.

Further research showed that 160756 had been built at Messerschmitt’s factory in Regensburg, Germany in late 1943 as part of a production batch from 160745 to 160770, with fuselage factory codes from KT+LA to KT+LZ applied, giving 160756 the code KT+LL. It was later delivered to Jagdgeschwader 4 (JG 4), where it was coded as Yellow 4. The aircraft was also classified as a G-6/R3, a long-range reconnaissance fighter with the capacity to carry two wing-mounted 300-liter drop tanks. The aircraft also had attachment points for a sand filter for its oil cooler to operate in desert environments, as well as pilot controls for the filter in the cockpit, though this device was not present on the NASM aircraft.

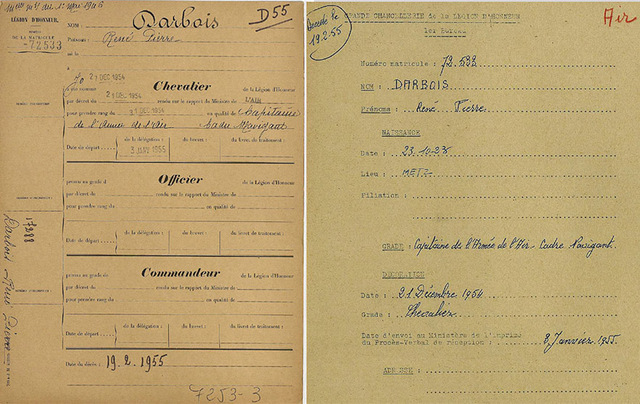

Then, in 1995, Jim Kitchens, an archivist at the Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell Air Force Base, Montgomery, Alabama, confirmed the identity of the pilot who flew Werknummer 160756/Yellow 4 to defect to the Allies as a French pilot named René Darbois. Details of his story have been seldom heard outside France, but it is an incredible story that deserves wider recognition.

René Darbois was born on October 23, 1923, in the city of Metz, and raised in the commune of Cocheren. He was noted by his friend Oscar Gérard as being quiet and reserved but having a strong moral character. Darbois would develop an interest in all things mechanical, especially aviation. However, the region of France that Darbois was born into was Lorriane, much of which had only recently been gained back from Germany following the First World War, which had taken parts of Lorriane and nearly all of neighboring Alsace after the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), and local tensions remained in place.

But with the rise of Nazi Germany and its policy to reunify all German territorial claims, many in Alsace and Lorraine feared that it would only be a matter of time before they would be annexed. Their suspicions proved valid following France’s defeat in 1940.

In Alsace and Lorraine, Germanization efforts were even stricter under the Führer than they were under the Kaiser, and young men from the two regions were subjected to conscription into the Wehrmacht, and boys under 18 were mandated to join the Hitler Youth. Despite his pro-French and pro-Lorraine sentiments, René decided that he would try to be accepted into the Luftwaffe and use the flight training it would provide to defect to the Allies and help liberate France and Lorraine. Upon being inducted into the Wehrmacht, Darbois joined the ranks of a number of men from Alsace and Lorraine who came to be known as the Malgré-Nous (the “Despite Us”). In the meantime, however, he would try to resist where he could without being detected. Before joining the Luftwaffe, he would clandestinely listen to BBC broadcasts, a crime punishable by death, while he was forced to finish his schooling with Gérard under Nazi doctrines in Phalsbourg, which was officially referred to by the German name Pfalzburg.

By the end of 1942, Darbois became a champion pilot on training gliders such as the SG 38 Schulgleiter (School Glider) as a member of the Nationalsozialistisches Fliegerkorps (NSFK; National Socialist Flying Corps), a paramilitary organization that instructed youths in aviation, with the goal of preparing them for Luftwaffe service. On March 2, 1943, Darbois received his Luftwaffe mobilization orders to begin basic training at Fliegerhorst Oschatz in Saxony. The training was grueling for all of the cadets, but Darbois was often singled out by the German instructors and his loyalty constantly questioned. Determined to complete the training, Darbois put on the appearance of accepting Nazi indoctrination in order to make good on his covert escape plan. Defecting from Germany, however, would be exceedingly difficult, for even if his plan was a success, the Germans threatened to deport the parents of defectors to a concentration camp, which only made him more determined to conceal his intentions and execute his plan to appear as if he had gone missing in action, as opposed to making an obvious dash to the Allies.

After completing his instruction on gliders, Darbois soon moved into powered training aircraft such as the Bücker Bü 181 Bestmann, Arado Ar 96, and even captured examples of the North American NA-57, which were originally built for the Armee de l’Air and subsequently captured and operated by the Luftwaffe. Darbois would also be sent all over the German Reich, from training with Luftkriegsschule 7 (Air Military School 7) in Tulln an der Danube just outside Vienna, to JG 103 in Stolp-Reitz, Pomerania (now Słupsk-Redzikowo, Poland), but his desire to escape from Germany remained unquenched.

His flair for acts of resistance would continue in the Luftwaffe, such as inscribing the Cross of Lorraine, a symbol of the Resistance, into his flying equipment and wearing a wristband with the symbol on his flights. Another act of passive resistance was when he was on leave in Paris in his Luftwaffe uniform. As he was entering the metro station tunnels, a man voiced his disdain at seeing a uniformed German, “We have seen enough of these Boches!” René whispered to him: “It won’t be long, old man!”

Having kept his acts of defiance subtle enough to deflect the occasional suspicion from his German superiors, Darbois was reassigned to Ergänzungsjagdgeschwader 1 (Supplementary Fighter Squadron 1) in Pomerania to qualify on the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and the Focke-Wulf Fw 190. These flights also took him over the German research center at Peenemünde on the Baltic coast, where Darbois would secretly take pictures of the V-1 and V-2 missiles under development there, as well as gaining information on the Messerschmitt Me 262 Schwalbe jet fighter.

Darbois knew the risks of being caught with this evidence, but he also figured that if he could smuggle the film with him on his defection, it would provide valuable information for the Allies. But in order to get himself to them, he would have to wait and see if his future posting would lead to a suitable place from which to escape. If he were to be deployed to the Eastern Front, he figured that the Soviets might execute or imprison him before he could explain himself, so he hoped to be deployed either to France or Italy, where he could make a successful flight to either the British or the Americans. During his training on the Baltic coast, he also pondered the idea of flying to neutral Sweden, but worried that even if he succeeded in landing there, he might be unable to leave the country to fight for France, and he worried about what might happen to his family back in Lorraine. But if there was one thing he was certain of, it was that in some way or another he was going to escape from Germany and save his country and family.

The wait to receive his new mobilization orders was agonizing, but to his great relief, Darbois, who was by now a non-commissioned officer (Unteroffizier), received orders to ship out to northern Italy and join up with Jagdgeschwader 53 (JG 53). However, upon arriving in Udine through the Alps by rail on June 30, 1944, he was informed that JG 53 was reassigned back to Germany to defend against Allied bombers just two days prior to his arrival. His heart sank, as he felt that his one chance to escape had been taken from him before his eyes. But in the meantime, he was to remain in Italy and would eventually be temporarily attached to Jagdgeschwader 4 (JG 4), which had been posted to Maniago, a small town in the foothills of the Alps, around 40 kilometers from Udine, on July 17.

When he had time to himself, however, he secretly studied his flight maps of Italy, pouring over the best routes and methods for his escape before he was to be called back to Germany, and calculating every possible factor, from how much fuel he would need to reach southern Italy to ways to avoid suspicion from both German pilots and official ground observers. It truly was now or never.

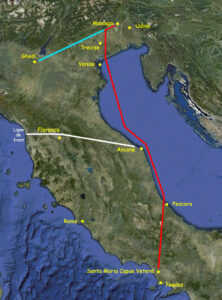

With orders to return to Germany arriving on the previous day, the morning of July 25, 1944 began with a briefing on a formation ferry flight for later that day from Maniago to Ghedi about 230 kilometers to the west, where the new pilots of JG 4 would then transfer their planes and baggage from JG 4 to remain in Italy with JG 77. The formation would consist of sixteen Bf 109s (fourteen G-6 single-seaters, and two G-12 two-seat, dual control aircraft). Though originally assigned to fly one of the G-12s, the other pilot of the G-12, Second Lieutenant Meyer, asked Darbois if he preferred flying another aircraft. After a short hesitation, he requested to fly one of the G-6s. The request was granted on the field. This pleased Darbois, as the G-12 had much smaller fuel tanks and no oxygen systems to make way for the second seat. What’s more, he was given permission to fly the commanding officer’s plane, coded Red 1. However, a faulty starter forced him to request another aircraft. He was granted permission to fly G-6/R3 Yellow 4, Werknummer 160756.

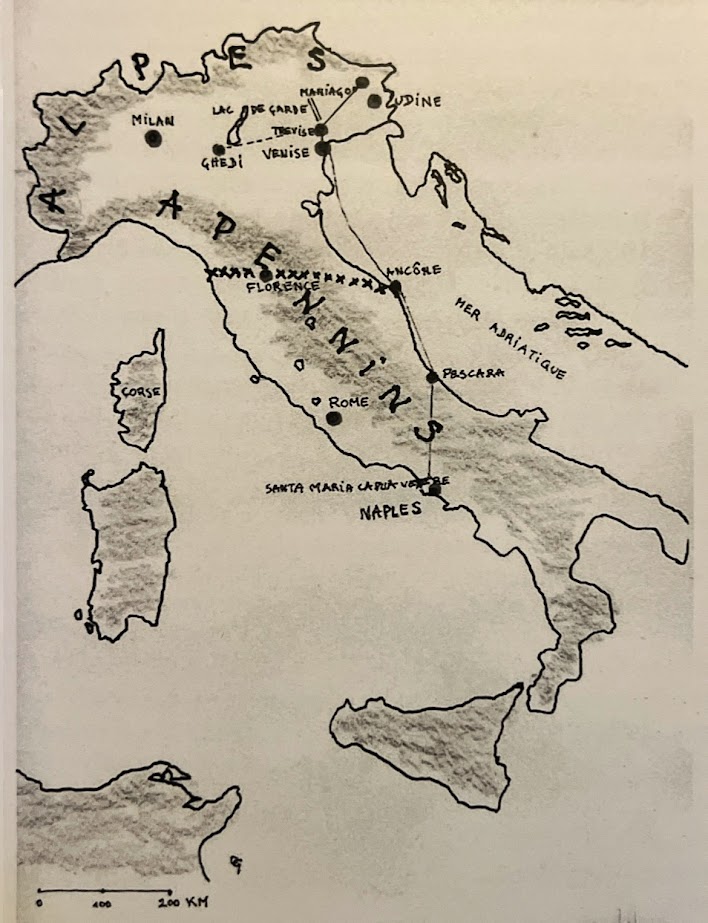

After taking off without incident at 3:35 p.m., the formation headed for their next waypoint on route to Ghedi under radio silence. At 3:55 p.m., Darbois flew up to Meyer and used hand signals to report that he was having mechanical difficulties and was requesting to land immediately. Meyer pressed his map to the canopy for Darbois to see and directed him to divert to Treviso, 20 kilometers to the south and just north of Venice. Darbois followed these instructions, but another Bf 109 from the group, following regulations, flew off his wing to ensure that he reached Treviso. Desperate to escape, Darbois signals the German that he no longer needs him and asks him to return to the formation. At first, the German refuses and stays with him, but Darbois was persistent, and once close enough to Treviso, the German pilot finally left to rejoin the formation heading to Ghedi. Once out of visual range of the other Messerschmitts and certain that he is no longer being followed, Darbois’ escape can finally begin.

To avoid detection, Darbois switched off his radio and transponder, and coaxed his Messerschmitt to gain altitude so that he would be both too high for ground observers to visually identify him and gain the best fuel efficiency possible at 8,800 meters (about 28,000 feet). One problem soon presented itself as he gained altitude; since the flight was not planned to exceed the designated ceiling of 500 meters (1,640 ft), the oxygen masks were removed by ground crews since they were deemed unnecessary. This presented a major problem for Darbois, who was trying to fly as high as possible, and as he climbed to 10,000 feet, then 20,000 feet, it became increasingly difficult to breathe and to swallow. However, the inlet tube from his oxygen tanks was still attached, and he clenched the tube in between his teeth to breathe. He was also wearing an Afrikakorps-style summer flight suit, which did not help him stay warm in the unpressurized cockpit. But he could make it to the Allied lines, then he could put up with this. But his thoughts also began to race for the safety of his parents back in Lorraine. Would they be punished for their son’s defection? While the fear of losing his parents hung over him with looming dread, he realized that he would have to get himself to safety before he could do something about his parents.

For much of the flight, Darbois flew on dead-reckoning, plotting his course along the Adriatic coastline with the map on his leg, and a wristwatch whose straps had broken, forcing him to hold it in his hand while flying the plane and scanning the skies for Allied fighters.

In addition to the removal of his oxygen mask, none of the pilots on the flight to Ghedi were issued any life preservers, as the flight was intended to be entirely over land. But with Darbois now skirting the Adriatic coast, he also pondered the reality that if he were forced to bail out over the Adriatic, he would certainly drown if there was no ship nearby to pick him up. But he forced those thoughts down as well and maintained his heading. At this point, problems arose with his propeller regulator, which shook the whole plane and forced him to reduce his speed to stay under control.

By 4:30 p.m., Darbois referred to his map and watch and determined that he was far enough over Italy to know that he was now over Pescara, which was well within Allied territory. Finally, he could descend below 10,000 feet and fly without needing supplemental oxygen. His intent now was to fly west from Pescara towards Rome, but to do that, he would have to navigate the valleys and ridges of the Apennine Mountains that constitute the spine of the Italian peninsula. To make things even more difficult, the Apennines were covered by clouds, and he would have to navigate the mountains on instruments.

By this point, having expended the fuel in his external drop tank, Darbois jettisoned it and flew on his internal tanks. Having lost his bearings in the clouds and the mountains, Darbois did not realize at the time that he was not flying west towards Rome but southwest towards Naples. No matter where he was though, he was determined to land at the first airfield he could find before running out of fuel, which happened to be a large one with two intersecting dirt and sand runways.

As it turned out, he had stumbled upon the airfield at Santa Maria Capua Vetere, near Caserta, just north of Naples. It was so far into Allied-held Italy that none of the men stationed this far south in Italy expected to see a lone German fighter. The only active unit there that day was the USAAF’s 72nd Liaison Squadron, equipped with Piper L-4 Grasshoppers and Stinson L-5 Sentinels. Surprised at the lack of anti-aircraft fire, Darbois reduces his speed, lowers his flaps and landing gear, and rocks his wings to signal his intent to land while circling overhead. Meanwhile in the wooden control tower on the ground, Corporal Davies, the signal lamp operator on duty, aimed his light at the approaching aircraft, whose markings he could not see at this point, and flashed a green signal light to Darbois. The markings on the wings and fuselage of Darbois’s Bf 109 were heavily camouflaged after arriving in theater, and the mysterious aircraft came to land at 4:45 p.m. Only after touching down did the personnel of the 72nd realize that a German Bf 109 had just landed at their base!

After coming to a stop at the intersection of the two runways, Darbois taxied the 109 to line up with a row of parked aircraft and shut the engine off. When the dense clouds of dust kicked up by the propwash began to settle, he opened a shutter in the canopy, signaling several bewildered soldiers to approach, but they stayed put. He then motioned for someone to help him open the canopy, as the frame’s heavy armor plating made it nearly impossible for Darbois to open it from the inside of the cramped cockpit.

An officer approached the canopy, and to Darbois’ surprise, he asked him in French, “Do you speak French?” The response was a quick “Yes!” It turned out that the officer was a French-Canadian, and with prompting from Darbois, he helped open the canopy. Emerging from the cockpit, Darbois removed his flying helmet and suspenders and asked that the markings on his plane be camouflaged to conceal the aircraft’s identity.

The American soldiers crowded Darbois and his airplane, and though they did not draw any weapons, they stared at him in curiosity. After explaining to the American soldiers through the French-Canadian’s translator that he was French, Darbois asked to see the senior officer at the airfield. Following the Canadian to a tent, Darbois met the senior officer, Major Percy, with whom he shared his name, rank, serial number, and reasoning for his arrival.

He also repeated his request that his plane be camouflaged with paint, so that the Germans would not identify it as his and retaliate against his parents in occupied Lorriane. While the aircraft was not repainted, several canvas tarps were placed over the wings, tail and propeller of the aircraft. Major Percy, however, listed Darbois as a deserter, to which he protested, insisting that he was an escapee, not a deserter, but his protests fell on deaf ears. For the time being, Darbois was held in custody at the airfield until he was sent to an improvised POW camp in Rome for further questioning.

After being secured by USAAF intelligence personnel, Yellow 4 was shipped to the United States for flight testing and evaluation against Allied fighters. Upon arriving in the U.S., the aircraft’s paint was stripped down to bare metal, though spurious German insignias were later applied to the aircraft. Being assigned to the Foreign Equipment Branch of the Air Technical Service Command’s Technical Data Laboratory at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, the aircraft was serialized as FE-496.

Most of FE-496’s flight tests for the remainder of the war would be conducted at Wright Field and Freeman Field near Seymour, Indiana. By 1946, the reincorporation of the Foreign Equipment Branch as the T-2 Intelligence Department would result in the aircraft being referred to as T2-496. Like many other captured Axis aircraft, FE/T2-496 was displayed at open house events and war bond drives for Wright Field and Freeman Field, such as the airshow held at Freeman Field in September of 1945.

By then, any association between T2-496 and the daring pilot from Lorraine was forgotten, but unlike many other captured aircraft that would meet their end at the scrapyard, T2-496 was lucky enough to be sent in May of 1946 to a former C-54 plant at Orchard Place Airport (now O’Hare International Airport), in the Chicago suburb of Park Ridge, under the auspices of No. 803 Special Depot, alongside other representative aircraft of both the Allied and Axis air forces intended for museum display. Most of the aircraft at Orchard Place were to join the Smithsonian’s newly-established National Air Museum, but with no permanent, dedicated building in Washington, the aircraft Park Ridge remained there until 1951, when one year after the outbreak of the Korean War, the Air Force reclaimed the plant and ordered the Smithsonian to move the collection out by January 15, 1952. This resulted in the establishment of the Silver Hill Facility and brings Yellow 4’s story back to the present.

As for René Darbois, following a short period of incarceration as a POW and losing most of the personal affects he took with him in the Messerschmitt, his requests to join the Free French Air Force were granted, and after spending time in Naples where his loyalty to France was initially questioned by his new comrades, he was sent to Algeria for flight training. To protect his parents, he was given a new identity, choosing the name Guyot, after an old family friend in Lorraine who was in sympathy with the Resistance. He was trained to fly Supermarine Spitfires, and assigned to Groupe ⅓ Corse (Corsica), and even served on several combat patrols over Germany before the end of the war. But even better for René, his parents in Lorraine were alive and well, and so was his friend Oscar Gérard, a former Malgré-Nous himself before defecting to join the Resistance and who was now a member of the French 2nd Armored Division under General Philippe Leclerc.

After the war, Darbois remained in the French Air Force as a flight instructor and a pilot in a precursor to France’s Patrouille de France, the Patrouille d’Étampes, flying Stampe SV 4 trainers in aerobatic demonstrations. But with the end of WWII came a resurgence in colonial independence movements across France’s overseas empire. Despite colonial forces being critical in the liberation of France, they were often sidelined by a government determined to maintain its control over those same colonies by force. In December of 1946, war broke out in Indochina (now modern day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia). It was a brutal guerilla war fought in the jungles, rice paddies, and cities and villages of southeast Asia that was to be a preview of the more prominent American-led intervention of the 1960s and 1970s. But by 1953, France was losing its grip on Indochina, and was sending more of its servicemen to keep the region under French control.

On October 6, 1953, René Darbois shipped out to Gary Air Force Base in San Marcos, Texas, for helicopter flight training. There, he learned to fly both the Hiller OH-23 Raven and Sikorsky H-19 Chickasaw, which he would soon use to fly on medevac missions in Indochina. Upon the completion of his training in January 1954, Darbois arrived in Saigon two months later and flew with Air Liaison Squadron 52 (ELA 52), based at Tan Son Nhut, just in time to help relieve a besieged French outpost at Diên Biên Phu.

Darbois made hundreds of flights in and out of Diên Biên Phu, carrying hundreds of wounded men from the battlefield. Braving small arms and anti-aircraft fire, and surrounded by the dead and dying, Darbois was often praised by his superiors, especially when on May 7, 1954, the day that Diên Biên Phu was overrun Vietnamese forces under General Võ Nguyên Giáp, Darbois evacuated 185 wounded under heavy fire. Darbois would also serve with similar distinction in ELA 53 and EHM 2/65 before a ceasefire was declared later that year. With the Geneva Conference that summer, Vietnam would be independent from France but divided between north and south along the 17th Parallel, setting the stage for the Vietnam War of the 1960s and 1970s.

But despite the praise from his superiors, and the fact that he would later learn that he had received a citation for the Légion d’Honneur (Legion of Honor) and the Croix de guerre des théâtres d’opérations extérieures (the War Cross for foreign operational theaters), Darbois was weakened by tropical diseases and the subsequent weight loss, and he was haunted by the brutality of this war, as he had been far closer to the action than he was in the Second World War. On December 21, 1954, Darbois finally embarked from Indochina for France to be reassigned.

The following January, Darbois returned home to his wife Jacqueline and their daughter Catherine. To all who knew him personally, though, Darbois did not return the same man they knew before Indochina, before Diên Biên Phu. In addition to the stress of combat and his physical ailments, he was also emotionally distant, with his friend Oscar Gérard reflecting that Darbois had returned with what today would be considered post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He was disinterested in the awards his nation sought to bestow on him, and on February 14, 1955, he was discovered dead in his home in Etampes, having taken his own life. He was 31.

The legacy of René Darbois would be preserved in several French sources, most notably in the memory of Oscar Gérard, who would dedicate his later years to writing the book Pilote de la Liberté (Liberty Pilot) about his childhood friend and other Malgré-Nous that he knew personally. But the further international outreach of Darbois’ story would not be possible without the chance discovery that the very same Bf 109 he had used to fly to freedom can be found in one of the world’s most visited museums. The ongoing renovations to the National Mall building in downtown Washington presented a perfect opportunity to return the Messerschmitt to the markings that it wore as part of JG 4 when a young Lorrainer finally had the chance to make a break for freedom. When its restoration in the Engen Hangar has been completed, it will be returned to the National Mall, where the upcoming Jay I. Kislak WWII in the Air Gallery (covered in a previous article here: NASM’s New World War II In The Air Gallery (vintageaviationnews.com)) is scheduled to open by 2026, where the memory of René Darbois will outlive the Thousand Year Reich.

To support the National Air and Space Museum, visit Homepage | National Air and Space Museum (si.edu).