Christopher Day and Dick Day question the value of the large investments made in Sydney’s metro system and its proposed developments.

Sydney is in the throes of a massive wave of investment in automated, stand-alone high-capacity metro railways. These technologies are tried and tested in very large and densely settled cities such as Hong Kong, Shanghai, Beijing and Taipei. Unfortunately, metro expenditure in Sydney is failing to relieve congestion on the existing rail system. Post COVID-19, changes in workplace commuting call into question the continued heavy expenditure on additional metro projects.

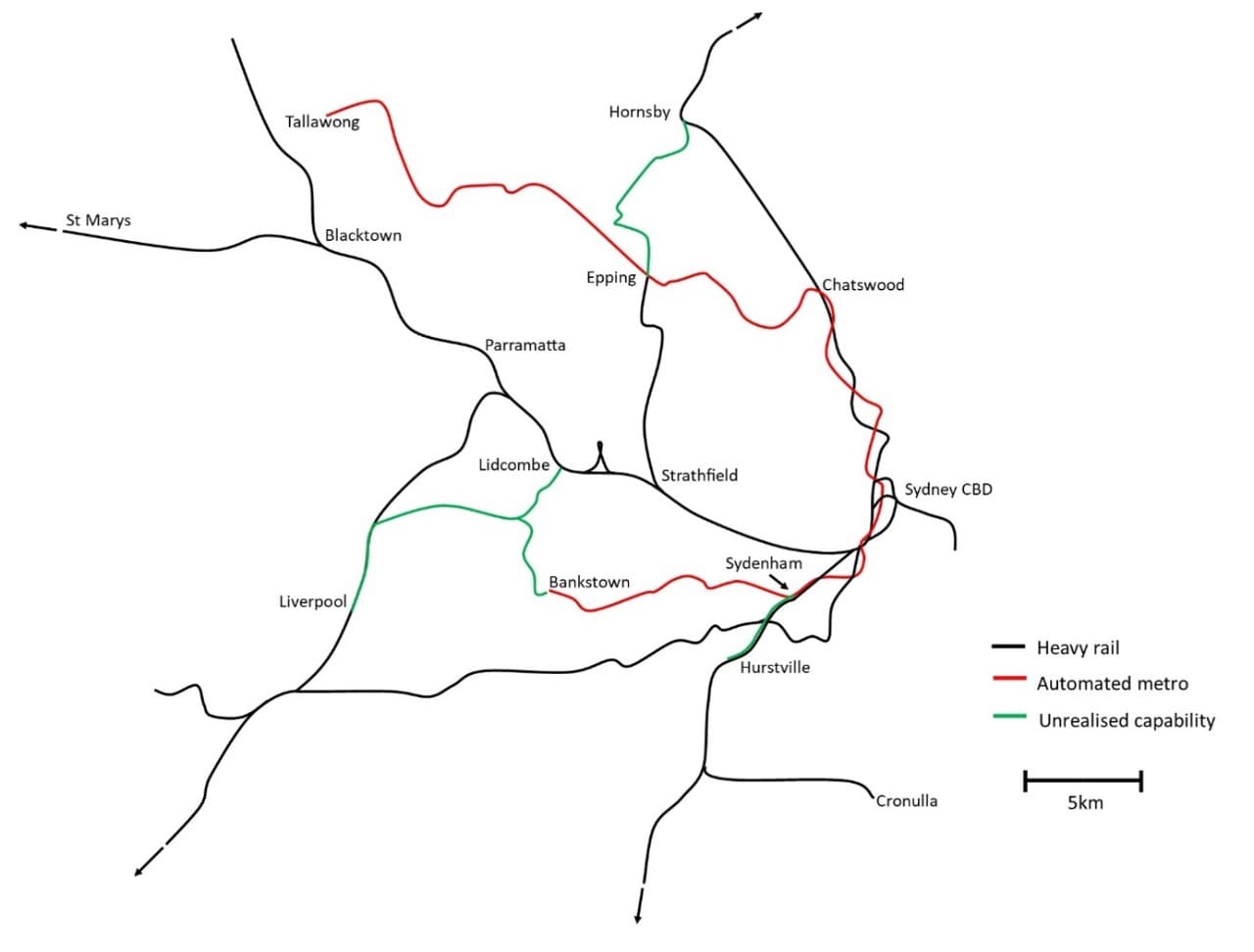

Metro implementation in Sydney has had bipartisan support. This ultimately metamorphosed into a government decision to construct the new railway line from Epping to Rouse Hill as an automated metro, as opposed to the initial plan to build it as an extension of the existing, conventional rail system. Simultaneously, the new line between Epping and Chatswood, then less than 10 years old, was converted to metro operation. From the outset it was proposed to extend the automated metro line through the CBD and, by conversion of an existing heavy rail link from Sydenham, onwards to a terminus at Bankstown, in the south-western suburbs. A proposed bifurcation from Sydenham to Hurstville was quickly abandoned when it was appreciated that the specialised metro operating requirements were incompatible with freight trains that shared the route. Subsequently metros have been adopted both to provide a circumferential link from the far western suburbs at St Mary’s to the site of Sydney’s second airport and to link the metropolitan area’s second CBD at Parramatta directly to the Sydney CBD. In both cases there has been an unprecedented rush by the government to lock in the construction of these projects despite a very poor understanding of their costs and benefits. This has taken place at a time when commuting patterns have shifted considerablyfollowing COVID-19, and the development industry is under intense resource pressure leading to very rapid price escalation.

This article questions the value of the current splurge on metro construction.

Sydney’s first metro: Tallawong to Bankstown

The new metro from Tallawong, in north-west Sydney provides a much-needed rail link to a broad range of destinations. However, the choice of an alternative technology has led to significant cost increases and passenger inconvenience which are less well documented.

Additional costs were incurred in four ways. Firstly, there was conversion of the recently completed existing line between Epping and Chatswood which involved considerable resignalling, major modifications to the overhead and electrical supply systems and platform modifications to suit the new metro trains. Secondly, there were significant costs in adapting the northern part of the existing North Shore Line to accommodate the extra trains needed to carry passengers alighting from the Metro at Chatswood and proceeding towards the city. This involved a difficult and expensive upgrade at Hornsby which will cease to be required when the metro extension to the CBD is completed. Thirdly, additional trains were required due to the forced change at Chatswood compared to conventional direct trains from the north-west sector to the CBD. Finally, there was a significant increase in rail congestion caused by rerouting Hornsby trains traveling via Epping onto their traditional and congested route via Strathfield.

A map of the Sydney rail network, including the North-West, City and South-West Metro is below.

The extension of the metro line through the CBD provides a much-needed increase in central area capacity. The Metro’s fundamental deficiency becomes apparent south of Sydenham and results in its inability to operate at more than half its achievable capacity, whilst limiting relief to the rest of the rail system. Unlike the Eastern Suburbs Railway extension of 50 years earlier, through which train diversion benefitted the entire rail network, the new Metro only gives effective congestion relief to trains operating from Bankstown, East Hills and Campbelltown. In order to achieve this more modest uplift the Bankstown Line requires extensive modification to cope with driverless metro trains. Furthermore, some stations beyond Bankstown lose their through service entirely whilst others will be forced onto the alternative and congested route to the city via Lidcombe and Strathfield making services from the Liverpool/Fairfield area of the city even slower than today.

Adoption of the original Metro plan, which incorporated additional services to Hurstville, would have afforded significantly greater benefit by relieving congestion on the Illawarra Line from Sutherland, Cronulla and the South Coast. It would also have taken up a significant amount of the endemic spare capacity caused by having only a single southerly connection from the Bankstown Line which, by any stretch of the imagination, is unlikely to ever produce more than 16,000 passengers in a peak one hour, even after massive, and perhaps unwanted, construction of additional high-rise apartments.

Underutilisation of the new CBD metro tunnel also applies to services from the north. The Metro indeed has the much-vaunted capacity to move at least 30,000 people per hour in each direction. Unfortunately, the entire north-west sector is unlikely to generate more than 16,000 boardings per hour in the foreseeable future.

Metro mania

With Sydney’s first metro far from complete, and at a time when COVID-19 has dramatically increased the rate of change away from traditional full-time CBD office employment, one might surmise that further metro adventurism would be firmly on hold. Instead, there has been a rush to commit to vast additional projects for which there is little rationale.

The proposed Western Sydney Metro is a north-south circumferential line with six stations connecting a relatively small suburban station in Western Sydney to the new Western Sydney Airport and putative third CBD, currently an undeveloped area to the south of the airport site. The cost is estimated at $11 billion!

The most basic understanding of mobility requirements makes it apparent that trips to the future airport and adjacent centre will come from a variety of directions and, initially at least, will be primarily by car. In these circumstances public transport access is best served by a network of express bus services linking both the airport and future city centre directly to the surrounding major nodes of Campbelltown, Camden, Liverpool, Parramatta, Blacktown and Penrith. Whilst reservation of fixed transit corridors is laudable, enormous expenditure on an isolated metro system that will see quite limited use is a gross misuse of public funds. Indeed, the Commonwealth infrastructure agency has questioned the decision, but to no apparent avail.

Undeterred the NSW Government is also pressing ahead with another metro line from Westmead and Parramatta eastwards to the centre of the Sydney CBD. Superficially this seems a worthwhile investment to ease congestion on Sydney’s busiest rail artery. However, even an initial examination makes it apparent that this will not be the case. The vast majority of rail passengers heading towards central Sydney from Parramatta have boarded their trains at the numerous stations further west and will not interchange onto the new metro which is projected to serve only one location in the Sydney CBD compared with six on the existing line between Redfern and North Sydney. The existing railway already boasts a three-minute service frequency in the peak period compared with the much touted four minute turn up and go frequency of the proposed metro! Whilst the West Metro will provide enhanced accessibility for a few areas around Olympic Park and Five Dock any benefit is dwarfed by the huge, but poorly articulated cost of the project, estimated at $26.6 billion. The only proposed station in the heart of the Sydney CBD will create enormous disruption in order to create a new rail link between the two CBDs of Parramatta and Sydney that in most cases will be less convenient as well as no quicker than the existing line.

In conclusion

Sydney’s metro mania comes with a lot of hype. In reality, it is destined to be an extremely expensive and poorly thought through experiment found wanting as a cost-effective means of enhancing the metropolitan area’s public transport network. Compare it with London, Melbourne or Brisbane where new railway tunnels through the heart of each city will accommodate existing train services at improved frequencies and provide relief for all of their existing networks.

Overall, the cost of creating Sydney’s deliberately non-compatible metro rail system, let alone the cost of imposing it onto existing trackage such as the Bankstown line, substantially outweighs any imagined benefits from removing train drivers, privatising by stealth or marginally reducing tunnel bore size through the core of the CBD. Sydney will be increasingly vulnerable to service disruptions where train services can no longer be diverted onto alternative routes. Worst of all our first metro lacks the feeder routes that would provide enhanced congestion relief to the rest of the network and is limited to a ridership which is no more than half that which such a high-capacity system could readily sustain. The Parramatta to Sydney metro is poised to repeat this failure.

We are at what may be a watershed moment in central area employment, with CBD workforces and most employers showing no desire to return to pre-COVID levels of occupancy. Whilst it would be naïve to assume that central area office employment will not trend back up through time, it is apposite to recall that the Sydney CBD was managing the pre-pandemic commuter task with no rail enhancements. Even in its constrained configuration the metro will provide the equivalent of at least a 15% increase in usable capacity. Given the very real possibility that peak CBD rail commuting will never return to pre-pandemic levels, it appears reckless at this time to commit vast sums of money on additional, and relatively ineffectual, enhancements.

How did the current situation come about and what can be done, if anything, to ameliorate it?

The last 15 years has seen a steady concentration of transport decision-making in the NSW Department of Transport, accompanied by a general deskilling of the specialised workforce previously responsible for managing the operation and development of the railway. There is a paramount need for comprehensive and informed analysis and discussion prior to critical, multi-billion dollar infrastructure investment decisions being made and a need to separate them from a largely unaccountable political environment. Unfortunately, there is little public pressure to embark on such comprehensive reforms.

Regarding the future of Sydney’s metro railways, the western Sydney airport link is clearly premature. There is also no immediate need for a west metro from Sydney to Parramatta. At the least it must be made interoperable with the existing railway west of Parramatta as this would enable significant capacity enhancements for the whole western corridor. With regard to Sydney’s first automated metro, the original concept of converting two of the tracks to Hurstville still has considerable merit. Unfortunately, adaptations that might permit through running from Hurstville are highly unlikely to prove contractually or financially acceptable.

Sydney University Review