When visitors to the Planes of Fame Air Museum make the turn to arrive in the museum’s parking lot, they are met by the site of one of the most iconic bombers of WWII, a B-17G Flying Fortress. But this Fort, serial number 44-83684, is not only on display and accessible to the public, but it is also a TV and movie that is an ongoing restoration project, with a small but highly dedicated team of volunteers that ultimately seek to restore this iconic aircraft to flying condition.

The B-17 currently standing in front of the museum on Cal Aero Drive is quite fittingly a local of Southern California. It was built under license from Boeing at Douglas Aircraft’s plant in Long Beach and in what would turn out to be out-of-the-production batches of the legendary Flying Fortress. The aircraft was accepted into the United States Army Air Force as 44-83684 on May 7, 1945, just one day before Victory was declared in Europe. With the war in Europe over and no need perceived for the aircraft in the Pacific, 44-83684 was one of the many planes at the end of WWII that flew from the factory to the boneyard. But rather than being cut up for scrap, the aircraft spent its first five years in storage in Texas, first in Lubbock, then at Pyote Air Force Base. In 1950, however, 44-83684 was revived to be converted into a DB-17G drone director as an element of the 3200th Drone Group at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. 44-83684’s new job was to guide unmanned QB-17Gs into the mushroom clouds of nuclear weapons tests to collect samples for scientific study. The DB-17Gs would fly a safe distance away from the radioactive fallout, with an onboard operator making adjustments to the QB-17’s heading. DB-17G 44-83684 would perform this task at Eniwetok Atoll during Operation Greenhouse in 1951.

Several other surviving B-17s were also members of the drone program, including a fellow Douglas Long Beach B-17, 44-83514, which now flies with the Commemorative Air Force as Sentimental Journey, which was also at Eniwetok during the Greenhouse tests. Following Greenhouse, the DB-17s and QB-17s were rotated stateside, and 44-83684 was reassigned to the 3225th Drone Squadron, 3205th Drone Group, at Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico. At Holloman, the newly-designated QB-17Ps were used as targets for new surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and air-to-air missiles (AAMs), while the DB-17Ps would keep the unmanned B1-7s steady. It was on August 6, 1959, that the last of these flights between DB-17s and QB-17s was flown out of Holloman. Over the White Sands Missile Range, DB-17P 44-83684 guided QB-17P 44-83717 until the latter was brought down by a Hughes AIM-4 Falcon missile fired from an F-101 Voodoo fighter. A few days later, a retirement ceremony was held for the aircraft, as it was the last B-17 in operational service with the US Air Force. Shortly afterward, it was flown to the Boneyard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Arizona. But its second stay in the desert was to be brief, as within a month, an enterprising young collector named Edward T. Maloney, founder of The Air Museum in Claremont, California, arranged with the US Air Force to loan the aircraft to his new museum.

In contrast to today, where most airplanes loaned by the Air Force to museums tend to be strictly for static display purposes, 44-83684, now registered with the FAA as N3713G, would be maintained in airworthiness and based at nearby Chino Airport, then a rural former WWII training airfield that was only just beginning to gain its reputation among the nascent warbird community.

The 1960s would be when The Air Museum would have the most active use with 44-83684, not only flying it for display purposes at Air Force events across the country but for its use in film and television work. No role for 44-83684 is more remembered now than its time in the ABC TV series 12 O’Clock High, based on the 1949 Gregory Peck film of the same name, starring Robert Lansing, Frank Overton, and Paul Burke among others. With the name Piccadilly Lily emblazoned on its nose, 44-83684 was filmed at Chino Airport, whose WWII-era buildings were made to resemble an 8th Air Force Base in England, which was home to the fictional 918th Bomb Group. But 12 O’Clock High was not 44-83684’s only appearance on TV or in movies. In 1968, the aircraft was one of three B-17s brought to Santa Maria, on California’s Central Coast, for the filming of The Thousand Plane Raid, released in 1969, flying as “Bucking Bronco.” During the filming sequences, 44-83684 made a very low-level pass over the field, with museum pilots Don Lykins and Bob Grider, and Ed Maloney joining them in the cockpit as an observer. The footage shows the old bomber skimming just above the ground at a minimum of 10 feet! Additional credits to 44-83684 include an episode of Black Sheep Squadron (Trouble at Fort Apache) and a cameo in the Lydia Carter Wonder Woman series. By the 1970s, the aircraft’s R-1820 engines were beginning to tire. With the museum having to focus on moving to different locations before settling down at Chino, restoring and maintaining numerous other aircraft as part of its ever-growing fleet lacked the funds to put 44-83684 back in the air. With her grounding in the 1970s, the aircraft would be used for static display purposes, with visitors going through its interior regularly, and its “12 O’Clock High” name was altered to “Piccadilly Lilly II,” complete with some nose art that was previously not a part of the aircraft’s olive drab and neutral gray paint scheme.

In 1999, the Planes of Fame Air Museum received the full title to 44-83684 from the National Museum of the USAF, making it the property of the POF. By 2006, the many layers of paint were stripped from the aircraft, and a dedicated team of volunteers set to work on the airplane’s exterior and interior. For several years, the tail stabilizers were removed, worked on, and reinstalled, along with the rudder and elevators. Up until now, much of the work on the tail, waist, radio, and navigator/bombardier sections has been completed, with the interior work now focused on the cockpit. Detail work is also regularly performed on the exterior, which pays tribute to not one, but two wartime B-17s.

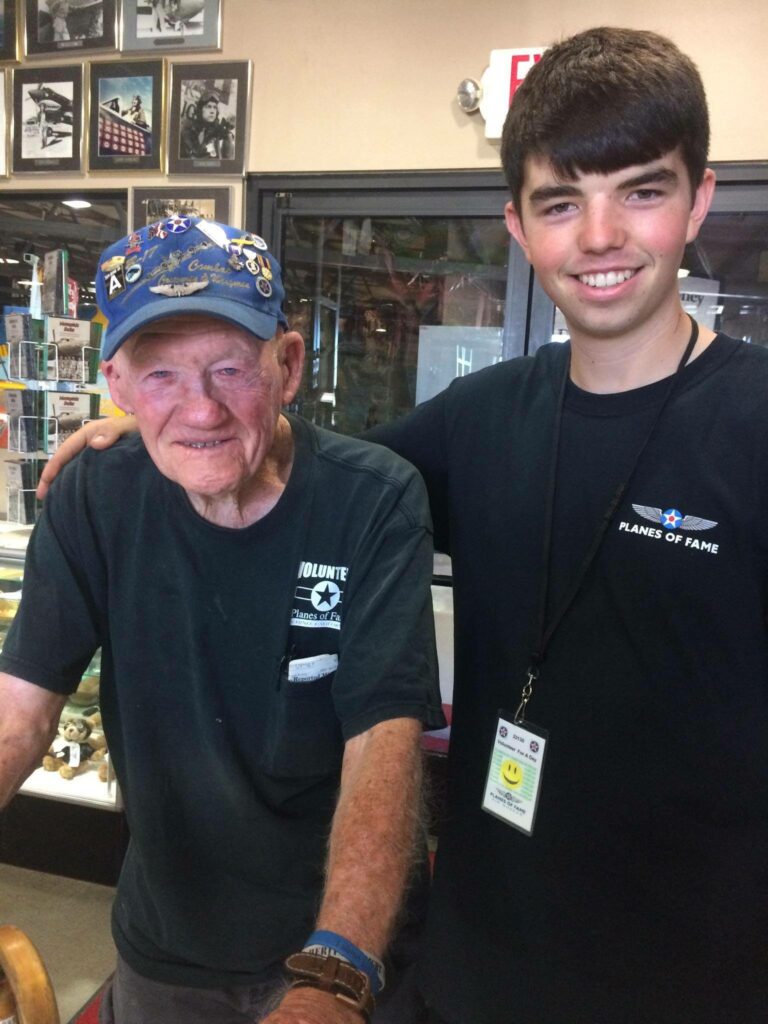

The left side of the B-17, 44-83684 sports the colors of B-17G 42-102605 “Kismet” (meaning fate) of the 331st Bomb Squadron, 94th Bomb Group, based out of RAF Bury St. Edmunds (now Rougham Airfield) in Suffolk. Longtime museum volunteer Wilbur Richardson served many of his 30 missions as a ball turret gunner on the original Kismet, which was later shot down over France on August 13, 1944, with a separate crew, and well after Wilbur was rotated home after being wounded in action over Munich on July 13, 1944. Wilbur was a regular volunteer on the B-17 Piccadilly Lilly II well into his mid-90s, and would often sit under the wing of the B-17 and tell visitors and fellow volunteers about his experiences as a ball turret gunner. (As a personal note, the writer of this article was close to Wilbur, having numerous opportunities to sit down and talk with him until his passing in 2020 at the age of 97).

The right side of the aircraft is painted in the markings of B-17G 42-97158 of the 338th Bomb Squadron, 96th Bomb Group, stationed at RAF Snetterton Heath in Norfolk, and was later damaged over Germany on January 5, 1945, making a forced landing in a field near Remagne, Belgium, within American lines. Among the men who flew on this aircraft before its final mission was navigator John “Jack” Croul, who would later become the co-chairman of Behr Paint. In his personal life, Croul was also an avid car and aircraft collector and would later found Allied Fighters, which is based both out of Chino and Haily, Idaho. Allied Fighters is most famous for the P-38 known as Honey Bunny, and the P-47 Dottie Mae, which was recovered from an Austrian lake in 2005 and restored to flight in 2017. Croul made a large donation to the Planes of Fame, and in honor of that, the right side of Piccadilly Lilly II has been painted as 42-97158.

As of 2024, work on 44-83684 remains slow but steady. Much has been done over the twenty years, but with a small volunteer crew largely working off of donations, there is still much to be done before Piccadilly Lilly II/Kismet can be considered airworthy. One of the leading volunteers on the project, Bill Amend, was kind enough to provide some insight into what has been done already and what remains:

“A team of volunteers tasked with the restoration of the aircraft was put together in late 2008. Prior to that, maintenance and some minor restoration work was mainly done on an informal basis by the docents. The restoration team has varied in size from as few as four members to nearly a dozen as various volunteers come and go. Most work on the aircraft is done on Saturdays when the aircraft is simultaneously open for viewing by museum visitors. However, some tasks, particularly those involving woodworking (making ammo boxes, instrument panel frames, floor sections, etc.), are performed by volunteers in their home workshops.

While the longer-term objective is to return the aircraft to flight-worthy condition, the initial objective includes two parts:

1) Refurbish the interior to a typical WWII combat condition to enhance the visitor experience, and

2) Improve the weather-tightness of the fuselage.

Southern California weather conditions are not extreme, but temperatures reach more than 120o F in the nose section in the summer, and because of various incomplete repairs and modifications that were made before formal restoration started, the plane leaks badly in the rain. Seasonal Santa Ana winds blowing up to 50-60 mph push dust and dirt through every opening. As a result, some interior features have had to be restored more than once. Furthermore, some restoration time is lost in the process of having to “visitor-proof” the interior by fabricating and installing additional acrylic barriers and signage to prevent entry into some areas or by having to repair unintentional wear and tear and even vandalism that has occurred by visitors. The work began with photo documentation of the condition of the aircraft interior. Those photos served as a visual reference to what the team started with and supported ‘before’ and ‘after’ comparisons of the various compartments. Next, most of the equipment and accessories on the interior were removed so that the interior could be cleaned, stripped of paint, and repainted. An inventory system was devised consisting of a photographic catalog of the parts, a log of which parts are stored in which boxes (boxes were numbered), and where at the museum the boxes were stored. In preparation for reinstallation, parts are gradually retrieved from the boxes and refurbished to their original condition. In some cases, we have been able to locate new old stock (NOS) parts on the open market rather than refurbish deteriorated or damaged parts. Although, when possible, original parts are reused. When the radio operator’s desk was refurbished, it was disassembled and some of the wood pieces were re-used instead of being re-made. We also maintain close liaison with some other B-17 restoration projects. For example, Hangar 13, with whom we trade information and duplicate parts. The 91st Bomb Group Memorial Association has been generous with donations, including radio equipment in excellent condition.

When parts are missing or need replacement and are not available on the open market or through our trading network, they are fabricated and installed according to original parts drawings and assembly drawings. Obtaining the correct drawings from the set of over 13,000 scanned drawing images can be challenging since neither the drawing index nor the part number list is electronically searchable. That means the user needs to know either the part number or the correct name of the part to find the correct drawing. The process is further complicated because part or assembly details can vary not just among B-17 models (i.e., F model vs. G model, for example), but also within ranges of aircraft serial numbers; not all B-17 models have the same parts or assembly details. Only some temporary replacement parts, such as cockpit windows, are not airworthy and are currently installed to promote weather-tightness, rather than being a long-term, permanent repair. The PoF B-17 benefits from having been received directly from the Air Force. It was never converted to a fire bomber or other civilian service. Consequently, most of the interior details are original. However, it can become a challenge to sort out original 1945 details from equipment modifications that were made during post-war AF service as a drone director. For example, some details of the navigator desk, the APU support, and some radio equipment details were original to the AF service but had been modified after 1945. The restoration process is tracked on the Piccadilly Lilly II Fan Club – B-17 Return to Flight Restoration page on Facebook. The group has more than 2300 members from over 10 different countries.”

As Bill mentioned, visitors are allowed and encouraged to visit and tour the B-17. On weekdays, the grounds around the aircraft are open, but the interior of the aircraft itself is typically open on weekends as the restoration team carries out its work. Museum docents (such as the author of this article) will guide visitors through the waist section and radio compartment, and the bomber’s nose, ball turret, and tail turret hatches are all opened for visitors to inspect from the hatches, and the bomb bay doors are opened during operating hours. Ultimately, however, the museum will eventually have to disassemble the aircraft to overhaul and restore its engines, propellers, wing spars, and other crucial components, which will require more support to accomplish. Little by little, restoration volunteers and docents alike do their part to return Piccadilly Lilly II/Kismet to operational status, and no matter how long it may take, so long as there are donations and volunteers, work will continue on the Planes of Fame’s B-17.

For more information, visit Home Page | Planes of Fame Air Museum to see how you can be a part of Piccadilly Lilly’s story.

Many thanks to Bill Amend and all of the restoration volunteers for their efforts in restoring Piccadilly Lilly II.