U.S. officials are privately delivering an unusual warning to telecommunications companies: Undersea cables that ferry internet traffic across the Pacific Ocean could be vulnerable to tampering by Chinese repair ships.

State Department officials said a state-controlled Chinese company that helps repair international cables, S.B. Submarine Systems, appeared to be hiding its vessels’ locations from radio and satellite tracking services, which the officials and others said defied easy explanation.

The warnings highlight an overlooked security risk to undersea fiber-optic cables, according to these officials: Silicon Valley giants, such as Google and Meta Platforms, partially own many cables and are investing in more. But they rely on specialized construction and repair companies, including some with foreign ownership that U.S. officials fear could endanger the security of commercial and military data.

The Biden administration’s focus on the repair ships is part of a wide-ranging effort to address China’s maritime activities in the western Pacific. Beijing has taken steps in recent decades to counter U.S. military power in the region, often by seeking ways to stymie the Pentagon’s communications and other technological advantages in case of a clash over Taiwan or another flashpoint, officials say.

U.S. officials have told companies, including Google and Meta, about their concerns that Chinese companies could threaten the security of U.S.-owned cables, a person familiar with the briefings said. In some cases, the conversations have included discussion of Shanghai-based S.B. Submarine Systems, the person said.

Senior Biden administration officials have also received briefings in recent months about the risks posed by Chinese companies, including SBSS, working on repairs to undersea cables, according to the person.

The security of undersea cables “is rooted in the ability of trusted entities to build, maintain, and repair” them “in a transparent and safe manner,” the National Security Council said in a statement, noting that satellite ship tracking “is one such measure that supports vessel monitoring and safety.”

The administration declined to comment on SBSS. Google and Meta declined to comment about the Biden administration’s concerns related to SBSS. SBSS didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The gaps in the company’s ship-location data could be explained by spotty satellite coverage rather than as an effort to hide their positions, according to another person who is familiar with the company. The cable owners often have representatives aboard repair ships at sea, which would make any potential meddling with cable gear hard to hide, the person added.

The vessels—named the Fu Hai, Fu Tai, and Bold Maverick—periodically disappeared from satellite ship-tracking services, sometimes for days at a time, while operating off Taiwan, Indonesia and other coastal locations in Asia, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of shipping data.

The data gaps were unusual for commercial cable ships and lacked clear explanation, the officials and industry experts said.

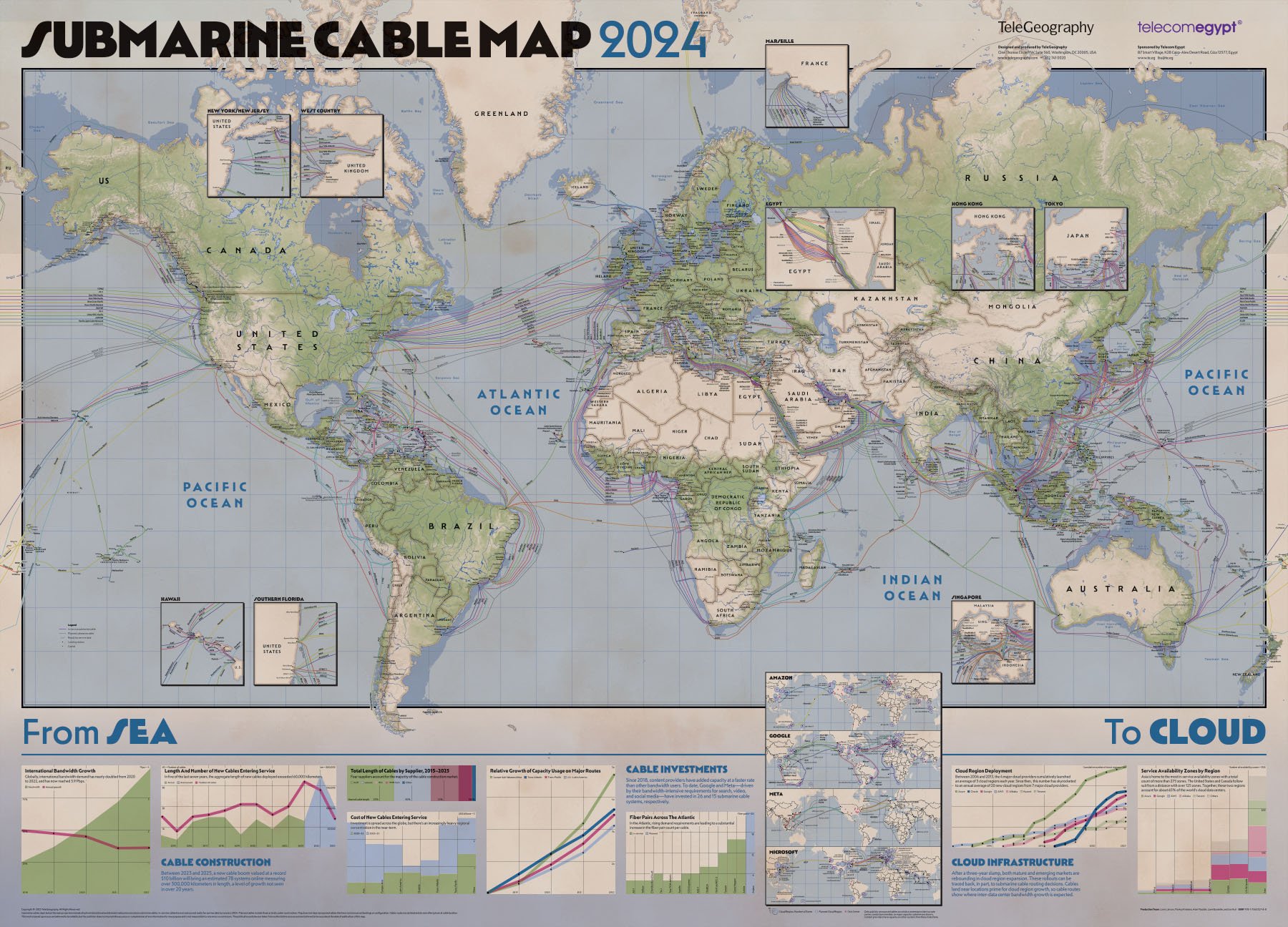

Hundreds of thousands of miles of underwater fiber-optic cables carry almost all the world’s international internet traffic. Dozens of lines lace the Pacific Ocean floor, shuttling data between the Americas, Asia and many island chains.

Workers pulled an undersea fiber-optic cable from a ship anchored offshore to a beach in Minamiboso, Chiba Prefecture, Japan, in 2012 as part of an operation to lay a cable connecting Japan and Singapore. PHOTO: KYODO NEWS/REUTERS

SBSS is part of a regional consortium of companies that provides ships to fix undersea cables, including some belonging to major U.S. companies, by winching them to the surface, resplicing broken fibers that carry internet data and returning the lines to the sea floor.

U.S. and congressional officials who disclosed their concerns about SBSS wouldn’t say whether their worries stemmed from classified intelligence about maritime espionage or only potential threats to internet infrastructure. But commercially available satellite tracking data showed numerous gaps while the company’s ships were at sea, they said.

Underwater cables are vulnerable to tampering when they are brought to the surface for repairs, U.S. officials say. Tapping global data flows is still far easier on land, industry experts say. But at-sea repair could still offer an opportunity to install a device to remotely disable a cable or to study the technology in advanced signal repeaters installed by other companies.

U.S. officials said that cable repair ships pose a security threat because they could engage in clandestine tapping of undersea data streams, mapping of the ocean floor to conduct reconnaissance on U.S. military communication links, or theft of valuable intellectual property used in cable equipment. The ships could also lay cables for the Chinese military, they said.

Liu Pengyu, a spokesman for the Chinese Embassy in Washington, said he wasn’t aware of U.S. concerns about SBSS.

“It is nothing wrong for Chinese companies to carry out normal business in accordance with the law,” he said. “We firmly oppose the U.S. to generalize the concept of national security and attack and smear Chinese companies.”

The SBSS vessels’ location-tracking beacons have been inoperative periodically over the past five years, according to radio and satellite data from commercial data provider MarineTraffic that was reviewed by the Journal.

In early February 2021, the Fu Hai left its berth near Shanghai and sped north up the coast into the Yellow Sea. Then the 340-foot, red-hulled vessel stopped broadcasting its location signal for two days before it popped up back near Shanghai. The signal went on and off for a few more days back near Shanghai before the ship docked again, tracking data show.

It wasn’t clear whether the vessel’s automatic identification systems—satellite and radio transponders that ships use to broadcast their location—were turned off or suffered an unintentional outage.

The Fu Hai has seen other significant gaps in reporting its tracking data at least a dozen times over the past five years, according to the MarineTraffic data.

A gap in transponder data alone isn’t necessarily a red flag, a senior U.S. government official said. “But it would raise suspicions if it happens repeatedly, especially if they are operating in the vicinity of a cable that might have strategic significance,” such as those ferrying military communications, the official said.

The U.S. intelligence community has warned for years about the security of undersea cables, noting in a 2017 report that industry consortia that maintain cables might “present vulnerabilities” and could be “susceptible to threats from insiders.” Cable integrity has long been a U.S. concern in the event of a direct conflict with China, former intelligence officials said.

SBSS was formed in 1995 as a Chinese-British joint venture. State-owned China Telecomhas long held 51% of the business and is in the process of buying the remainder from U.K.-based Global Marine Systems, according to people familiar with the matter. A member of the Chinese Communist Party serves on the SBSS management team, according to the company’s website. He didn’t reply to a written message seeking comment.

The U.S. in 2021 stripped China Telecom’s licenses, arguing that it was subject to “exploitation, influence and control by the Chinese government.” The move didn’t affect U.S. companies’ ability to use the repair consortium that includes SBSS.

Safeguarding underwater cables has been a focus of U.S. national-security officials since the Cold War, when fears of Soviet espionage were paramount. In the 1970s, the U.S. secretly placed wiretaps on underwater Soviet lines in an intelligence coup known as Operation Ivy Bells.

Beijing’s rapid military buildup in the South China Sea in recent decades has heightened American government worries about the cables’ vulnerability to disruption or tampering.

U.S. officials say they are especially concerned about the security of cables that carry sensitive data to American bases and other military assets in the Pacific and around the globe. Though encrypted, that data can pass through commercial internet lines.

To prevent interruptions from damaged lines, the U.S. government is funding several Pacific cable projects along with American internet companies, such as Google. Google this year said it was investing $1 billion in new cables and other infrastructure projects in the region.

SubCom, a cable ship company owned by private-equity giant Cerberus Capital Management, receives $10 million in annual U.S. government payments for participating in the Cable Security Fleet, a program partly overseen by the Pentagon. It requires the ships to be available for critical cable repair or other emergencies.

At a congressional hearing in January, Rep. Ann Wagner, a Missouri Republican, said she was “very concerned about Chinese companies repairing or even having access to undersea cables that are owned by U.S. carriers.”

Nathaniel Fick, the State Department’s top cybersecurity official who was testifying at the hearing, said he shared her concern. “I believe when our adversaries tell us what they intend to do, we should believe them,” he said.

Fick said in a statement to the Journal that undersea cable security can’t be assured if the lines “are built, maintained, or repaired by suppliers who are subordinate to or are beholden to authoritarian governments.”

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

What should the U.S. do to address security concerns related to undersea internet cables? Join the conversation below.

SBSS is one of three maintenance shipowners that are members of Yokohama Zone, a consortium used by internet cable owners in the northwest Pacific. The group keeps ships on standby, based in China, South Korea and Japan. SBSS parent China Telecom hosted a meeting of Yokohama Zone companies in Wuhan, China, in March, according to people familiar with the event.

In response to questions about SBSS, Yokohama Zone Chairman Masanori Araki, a submarine cable expert from Japanese telecom company and shipowner KDDI, said the Chinese company is in compliance with the consortium’s performance standards.

“Cable owners are receiving and enjoying assured service quality, whichever service provider they may use,” he said.

Industry analysts say that shifting responsibility for fixing Asian cables away from Chinese vessels could pose a tougher challenge. Cable owners have few choices among an aging fleet of roughly 50 ships around the world, according to Mike Constable, who runs telecom consulting firm Infra-Analytics and previously led China’s Huawei Marine Networks, now known as HMN Technologies.

“You’ve got a Chinese asset repairing U.S.-invested cables,” Constable said. “No one had really thought about that before.”

Write to Dustin Volz at dustin.volz@wsj.com, Drew FitzGerald at andrew.fitzgerald@wsj.com, Peter Champelli at peter.champelli@wsj.com and Emma Brown at Emma.Brown@wsj.com

Wall Street Journal