Track Access Charges (TACs) are on the rise in many European countries. For many rail freight operators this is a massive burden that could threaten their very existence, as their Ability-to-pay is basically null. RailFreight.com had a chat with Andrea Giuricin, transport economist at the University of Milan Bicocca, to better understand this trend and its impact.

“Increasing TACs seems a little counterintuitive as it makes it harder to reach the goals set by the EU”, Giuricin mentioned. On one side, there are Infrastructure Managers (IMs) which might need the money to cover investments and expenses. On the other hand, there are rail freight companies that often struggle to make a profit but still need to pay high TACs to run their trains. “All the big state-owned rail freight operators in Europe are losing money, I cannot see their Ability-to-pay”, he added.

To add insult to injury, the next few years will be characterised by many infrastructure upgrades all over the Old Continent. This means that many lines across Europe will be partly or not available for at least the next couple of years. “The rail freight industry in Europe is a sector struggling to make significant margins, and adding all the infrastructure works will not help”, Giuricin explained. Without any concrete financial help throughout this transitional period, rail freight operators might not survive.

How are TACs set?

For many European countries, TACs are set by national regulatory bodies in consultation with the IMs. The IMs communicate their fixed costs, such as wear and tear expenses, and then ask the regulatory body to calculate Ability-to-pay for the different segments (freight, high-speed, regional services etc…). Track Access Charges are then set based on the outcome of these results.

However, as the case of Germany shows, this is not always a smooth process. Here, the Bundesnetzagentur, the regulatory body tasked with setting TACs, is facing a massive backlash after announcing that the fee would increase by 16.2 per cent. Eleven German rail companies, including the IM DB InfraGO, are taking the Bundesnetzagentur to court to try and stop this initiative.

‘Only a political choice will help’

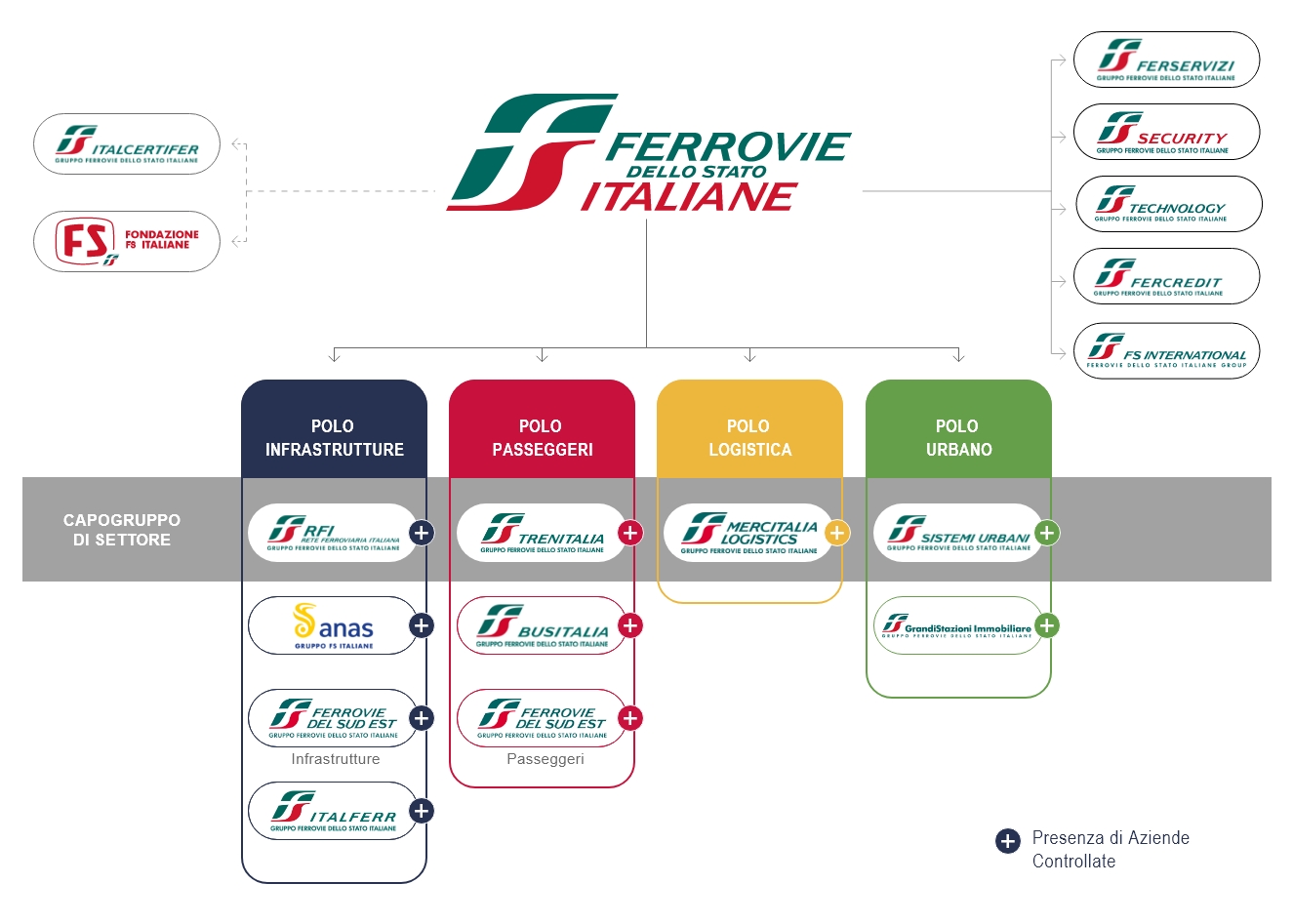

As Giuricin mentioned, the best way to help rail freight companies stay afloat would be a political choice. More specifically, governments should take the lead and compensate their country’s IMs for the rail freight sector’s (in)Ability-to-pay. Giuricin used Italy as an example, where TACs are made up of two components: Part A, which includes the IM’s fixed costs, and Part B, which concerns the various sectors’ Ability-to-pay.

“On average, TACs in Italy count for 10 to 20 per cent of the total cost for rail freight operators, making it a significant expense”, he said. What could help the Italian sector is a policy that was implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic and lasted until 2022. According to Giuricin, a budget of 60 to 70 million per year until 2026 should do the trick since, after that, many infrastructure upgrades will be commissioned.

During the pandemic, the Italian government decided to cover the Part B of the TACs to alleviate the burden on rail companies. The positive impact of this initiative was clearly visible, as data shows that the Italian rail freight sector managed to stay resilient throughout the years of the pandemic. However, the moment this subsidy was discontinued, things went south. As rail freight data for Italy in 2023 showed, there was a drop compared to 2021 and 2022, when the measure was still in place.

Also read: