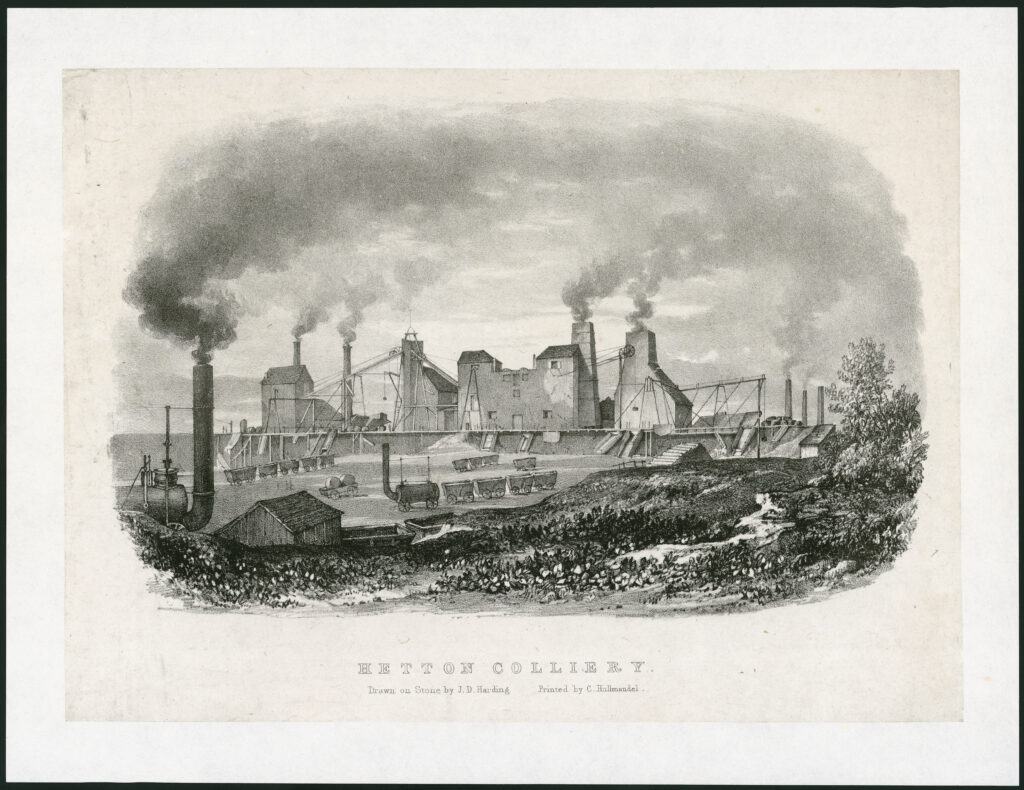

John Graham was 32 years old when he was selected from a field of 52 candidates to become Traffic Superintendent of the Stockton & Darlington Railway. Orphaned at an early age, he had worked in coal mining from the age of 10 and by 1822 had risen to become head underground overlooker at Hetton Colliery. This was the year which saw the opening of the Hetton Colliery Railway, engineered by George Stephenson. The eight-mile railway from pit-head to the staiths at Sunderland was of a revolutionary design, favouring a combination of steam locomotives, stationary engines and self-acting inclines over horse-drawn wagons. We must assume that it was here that John Graham gained the knowledge and experience required to take up the Stockton & Darlington post in the summer of 1831.

With his reports—written between 1831 and 1845 and comprising a total of 55,000 words contained in four leather-covered notebooks—Graham has left us with a unique insight into the day-to-day operations of the first public railway to use steam traction. The historic value of the notebooks is further enhanced by the handwritten annotations, comments and instructions by various directors of the company such as Edward Pease, Joseph Pease Jr and Henry Stobart.

Happily for the transcriber Graham writes in a generally clear, sloping hand with relatively few corrections and deletions. Occasionally the quality of handwriting suffers, presumably at times when the writer was under pressure to complete his report. His highly idiosyncratic spelling, grammar and punctuation can be initially disconcerting, though it soon becomes possible to attune oneself to the north-eastern cadences of Graham’s speech. He wrote as he spoke:

I have sent word to the Coal oweners that has been sending balast in there owen Waggons

3 Waggons went A main dowen the Black Boy north Bank

The report books are business documents and thus of no great literary merit—entries can be formulaic and repetitious, and Graham’s rather spare prose can create an overall impression of dullness. Yet this disguises the value of the books whose impact may be seen as cumulative rather than dramatic. For the reader with the stamina to work through the four volumes a picture gradually comes into focus of the railway’s evolution during its formative years.

Early entries reveal how Graham was confronted with a chaotic state of affairs when he first took up post—single line working with no signalling, a mixture of horse-drawn and locomotive-hauled coal traffic sharing the line with horse-drawn passenger coaches operated by half a dozen independent proprietors. There follows a litany of misdemeanours by hard-drinking waggoners who would think nothing of leaving horses and wagons on the line while they adjourned to the pub for a couple of hours. The enginemen, described by Robert Stephenson as ‘not the most manageable class of beings’, were scarcely any better behaved. Company directors are kept busy issuing fines or referring miscreants to the magistrate.

Gradually we see Graham get a grip of the situation, helped by improvements such as the doubling of most of the line, the phasing out of horse-drawn coal traffic and the buying out of the passenger coach contractors. His concerns begin to focus on the more technical aspects of operation—locomotive performance, broken wagon wheels, the state of the permanent way. He is constantly on the lookout for ways of saving the company money and always ready to adopt best practice to achieve this, an example being his recommendation to use wire ropes rather than hemp for the stationary engines, based on estimated savings of between 20 and 50 per cent.

Graham emerges from the report books as a practical man, receptive to new ideas and blessed with the virtue of sound common sense. He has been credited with the creation of the Shildon coal drops in 1847, two years after the final report book, but it is possible that the origins of their design lie in a visit to Hartlepool made by Graham in 1838 about which he noted that there was ‘nothing there worthy of Notice except the Drops which is Simple and Good’.

With his background in a tough and dangerous industry, Graham understood the importance of workplace discipline and there is ample evidence of his preparedness to dismiss anyone he deems ‘not fit to be in the Companeys Service’. At the same time he could include a plea for financial help with doctor’s bills from an injured fireman which secured the man a payment of £2 authorised by one of the directors, Joseph Pease Jr.

It is perhaps for the student of locomotive history that the report books have the most to offer. References abound to the acquisition, evaluation and performance of the railway’s motive power during this period. We see Graham travelling to loco builders in Leeds and Warrington to inspect prospective purchases. Telling details are revealed such as Graham’s recommendation that Alfred Kitching’s Queen locomotive (‘well made and finished’) be fitted with an extra pair of wheels to reduce loading on the light rails of the Middlesbrough branch. Similarly a loco from Neasham and Welch is rejected on the grounds that it would be ‘Injurious to the Railway’.

William Weaver Tomlinson was probably one of the first people to read the report books in their entirety for his magisterial book on the North Eastern Railway published in 1914. Many writers since him have relied on the extracts included in his work when making reference to Graham. With the availability of the complete original text of the report books online and a transcription in searchable digital format also available on request from Search Engine perhaps it is time to undertake a reappraisal of these documents and unearth more of the treasures contained within?

The catalogue records for the John Graham Report Books containing digitised images and the transcripts are available on the Science Museum Group’s Collections Online portal.

Find out more about contacting Search Engine, the National Railway Museum’s research centre, for the full searchable transcripts or to arrange access to the John Graham Report Books in person.

The post ‘Begs Leave to Inform’: Transcribing John Graham’s Stockton & Darlington Railway Report Books appeared first on National Railway Museum blog.