Original text and research by Chuck Cravens edited by Adam Estes

Over the past decade now, Aircorps Aviation of Bemidji, Minnesota, has gained a well-earned reputation for some of the finest restorations among the warbird community, from their restorations of P-51 Mustangs such as Thunderbird and P-47D razorback “Bonnie” (both of which being Golden Wrench Award aircraft) to their ongoing efforts to restore a rare Beechcraft AT-10 Wichita trainer. But another project that has now entered the shop at Bemidji is a Piper L-4H “Grasshopper”, a seemingly ordinary aircraft in comparison to the team’s previous experience with Mustangs, Thunderbolts, and even the odd Zero, but which has a remarkable story and is one of the latest examples of a true “barn find”.

As many aircraft restorers can attest to, finding a new project sometimes comes to a chance discovery, and such was the case when Eric Trueblood, Senior Vice President of Marketing and Sales at Aircorps Aviation, decided to go on a bike ride with his daughter in Grand Forks, North Dakota, about a two-hour drive west of Bemidji. Along their ride, Trueblood spotted a Beech C-45 in an outbuilding and contacted the property owner about the aircraft. As it turned out, there was another aircraft in storage on the property. It turned out to be a Piper L-4H WWII liaison aircraft, with an initial look at the data plate suggesting it to be serial number 44-7879. Trueblood then contacted Pat Harker, who has restored and collected several award-winning liaison aircraft, from a Stinson L-1 Vigilant to a Convair L-13, but up to that point, he did not have an L-4. With Harker’s interest in the project, the L-4 was purchased and shipped to Bemidji for restoration, where its personal history would begin to reveal itself.

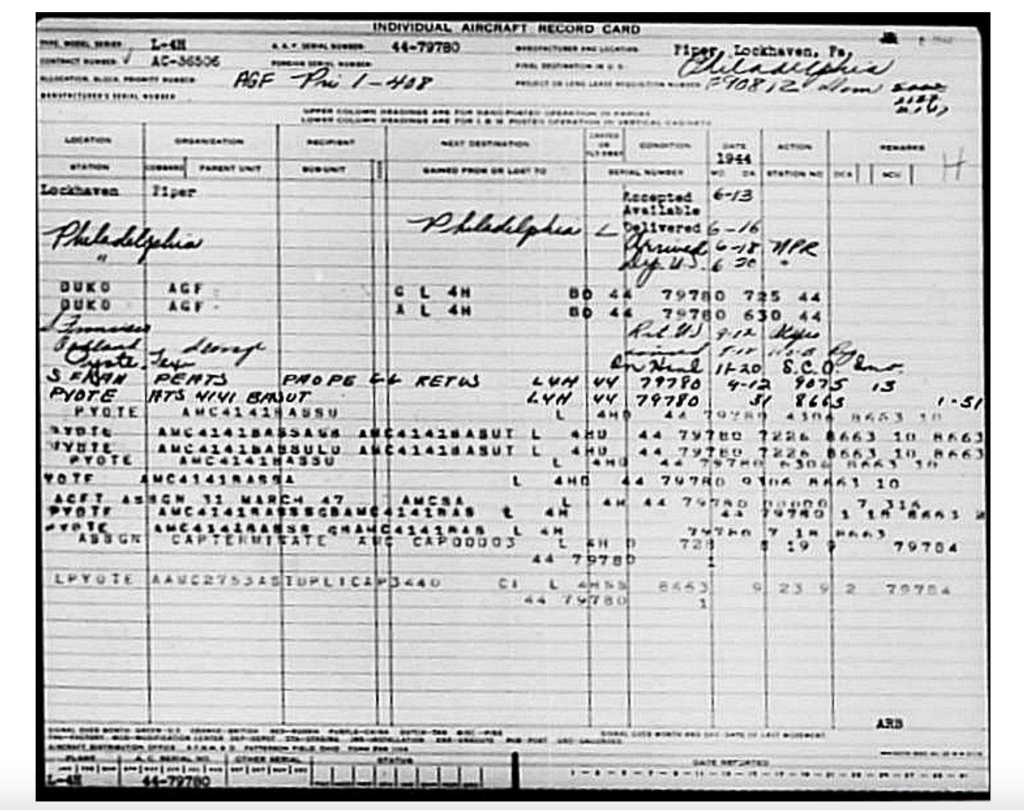

The previous owner of the L-4, Daniel Romuld, also granted access to the research materials and letters he had made up to that point on the aircraft, which he had registered with the FAA as N86506, but he had been largely unsuccessful in finding much of anything on the history of the L-4. As it had turned out, the L-4H now at Aircorps’ shop was not 44-7978. Upon cleaning the rusted data plate, it was discovered that the aircraft’s complete serial number was in fact 44-79780 and that further research revealed that 44-7978 was the serial number of a Curtiss P-40N Warhawk. Another error made on account of the condition of the data plate before cleaning work was that the Contract Number (or Order Number) was believed by Romuld to be AC-86506 when in fact it was AC-36506. This detail along with finding the correct serial number would be critical in obtaining the Individual Aircraft Record Card (IARC) from the Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell AFB in Alabama.

Upon receiving 44-79780’s IARC, Aircorps received some much-appreciated assistance from James H. Gray, founder and president of the Sentinel Pilots and Owners Association and a well-known liaison aircraft expert. With many of the terms and abbreviations on the IARC being unique to liaison aircraft, Gray’s expertise proved to be invaluable.

Being constructed at Piper’s Lock Haven, Pennsylvania plant, the L-4H built as manufacturing number 12076 was accepted into the US Army Air Force as 44-79780 on June 13, 1944. Within three days, the aircraft was packed into a crate and shipped to Philadelphia, where it was noted as arriving in the city’s port on June 18. Just two days later, the aircraft was on a ship bound for Naples, Italy, which it was assigned to the Twelfth Air Force, Army Ground Forces on June 30, being fully under the jurisdiction of the Army Ground Forces on July 25. For the remainder of the war in Europe, 44-79780 performed dutifully and humbly. However the next record of the aircraft does not appear until September 12, 1945, with the aircraft having arrived in San Francisco via the Pacific Ocean. Gray summarized his interpretation of this data point with the following statement: “As far back as 1943, plans were begun for demobilization as soon as the war was over. Part of the procedures included ending war material production and stopping all ships from leaving U.S. ports loaded with more troops and equipment. Those already bound for the Pacific were to be halted and brought back to the States if they were less than halfway to their destinations. A study of shipping timetables shows that the time at sea for a fast freighter (14 knots) was 20 days from Naples to the Panama Canal (6,600 nm) and another 15 days to Hawaii (5,100 nm). The war ended on Sept. 2, so I’m speculating that by then the ship carrying 44-79780 was already in the Pacific Ocean, but less than halfway to its final destination (somewhere beyond Hawaii) when it was suddenly turned around and diverted to SFO. If this was not the case, it would not have ended up in San Francisco, it would have been returned from Europe by the cheapest and most direct means to an East Coast or Gulf Coast port.”

It is also possible that had the vessel carrying 44-79780 been loaded with troops returning from Europe, it could have been diverted to San Francisco if the processing centers and trains on the East and Gulf coasts were overcrowded with returning servicemen, that the ship was needed immediately for duties in the Pacific, or that nationalized National Guard units from one of the western states may have been onboard and it was more convenient for them to arrive in a West coast port or that there were personnel that were to be redeployed to the west coast. Whatever the reason, the record clearly states that after serving in Europe, 44-79780 returned to the United States through San Francisco. It would also be in the Bay area where 44-79780 would be kept in storage in Oakland from September to November of 1945 before being sent to Pyote Army Airfield in Texas, where it would stay until it was assigned to the Civil Air Patrol on July 28, 1949, with the last date entered on its IARC being September 23, 1949. At some point during its time with the Civil Air Patrol (CAP), however, the aircraft suffered a forced landing. The aircraft’s time with the CAP and its subsequent incident is still being investigated, but when the aircraft was acquired by Pat Harker in the fall of 2023, its fuselage frame retained the damage sustained during this forced landing, and lines up with the historic photograph of the aircraft shortly after its crash landing.

With the restoration still in its early stages, there will be further updates as the work progresses, but for the present moment, here is the latest from Aircorps Aviation: The tubular fuselage frame is to be sent to the specialists at Javron, Inc. of Brainerd, Minnesota for repair and restoration, while the wooden stringers will also have to be inspected for repair and restoration. The four-cylinder Continental A-65 (also known as the O-170) 65 horsepower engine that came with the project had been overhauled in the past, but the work was done far enough in the past to warrant a new overhaul before the aircraft was ready to fly again. The wings are currently stored at Aircorps’ hangar and await further work on both the wooden spars and wingtip bows and the aluminum truss ribs. As the restoration team at Aircorps begins the task of restoring this L-4H, it is also worth mentioning the origin of how the L-4 and Army liaison aircraft derived from light general aviation designs came to be called Grasshopper, and how the Piper L-4 played a key role in the development of and the terminology behind such aircraft.

Though military aircraft had always been developed with the idea of using the advantage of height to see what ground forces could not see, liaison aircraft are typically used to conduct battlefield reconnaissance, artillery spotting, and transporting commanders and messengers to the front lines. The interwar years had seen a series of army observation aircraft take flight to fulfill these tasks, and by the outbreak of war in Europe, the foremost of the so-called O-birds were the North American O-47 and the new Stinson O-49 Vigilant (later to be redesignated as the L-1), which were the results of Army Air Corps design competitions. But William T. Piper, president of Piper Aircraft, felt that light aircraft, adapted from general aviation designs such as his own J-3 Cub, could serve a greater use for Army ground forces than could aircraft such as the O-47. He would outline this proposal in a detailed letter written on February 18, 1941, to the Secretary of War Henry Stimson. After receiving this and other letters from competing manufacturers of light aircraft, the War Department decided to conduct a study on the effectiveness of light aircraft being used in support of ground operations. The following month, Piper and his employees wrote directly to several Army commanders.

Among these commanders was a Lieutenant Colonel with experience serving in the staff of General Douglas MacArthur. Having obtained a private pilot’s license, the Lt. Col. had personal experience with light aircraft, which he felt would be greatly useful as artillery spotters. That Lieutenant Colonel was Dwight D. Eisenhower.

To put these light aircraft to the test, the Army suggested that they be demonstrated at Fort Sill and Camp Bowie during the Second Army’s maneuvers in June 1941. The result was that the recommendations for light aircraft to be a regular part of the artillery were sent to the War Department. With the completion of the tests and studies at the end of April 1942, it was concluded that the light aircraft held several key advantages over heavier observation aircraft such as the O-47 and the O-49/L-1 for several reasons:

- They were easy for artillery field personnel to operate

- Their operational and maintenance needs were simpler

- They could be easily dismantled and loaded on 2½ ton trucks for ground movement

- With pilots also being qualified mechanics on these aircraft, each pilot was capable of repairing and servicing his own aircraft.

The light weight of the Pipers, Aeroncas, Taylorcrafts, and Interstates also lent to their operations from small fields and/or dirt and gravel roads, and their small size made them difficult to spot from the air and ground. The change in having light aircraft in coordination with Army ground forces also resulted in a change in designation from O for ‘observation’ to L for ‘liaison’, with Piper’s entry going from being called the O-59 to the L-4.

The L-4 was also the aircraft that resulted in all the light liaison aircraft being nicknamed “Grasshopper”, no matter their manufacturer. The story behind this involves a Piper company pilot and district sales manager Henry S. Wann, who had previously written to Lt. Col. Eisenhower to ask for support for the light aircraft program. While participating in maneuvers at Fort Bliss on the Texas/New Mexico state line, Wann was tasked with delivering a message to Major General Innis P. Swift, commander of the 1st Cavalry Regiment. Wann found Swift brigade against the desert backdrop, but with no improved field in the sand, cacti and clumps of grass, Wann made a bumpy but safe landing, taxiing up to the command post and delivering the message. Having watched Wann’s landing, General Swift remarked, “You looked just like a damn grasshopper when you landed that thing out there in the boondocks and bounced around.” Later on, after Wann and the Cub had returned to Fort Bliss, General Swift required the aircraft to return to his position, and sent the radio message “SEND GRASSHOPPER”. From there the name stuck, not only to the Piper L-4 like the one Wann had flown but to the Taylorcraft L-2, Aeronca L-3, and Interstate L-6.

With that anecdote, we hope to hear more from Aircorps Aviation soon and will provide their latest update when it is available. Until then, stay tuned for further updates at AirCorps Aviation | Vintage Aircraft Restoration & Fabrication | Aircraft Decals.