Which was the first city in Australia to get an electric tram network up and running?

Melbourne? Sydney? Nope. It was Hobart.

The small southern capital began operating its network in 1893 — years before the Sydney and Melbourne networks went fully electric.

In its heyday — the 1930s and 1940s — the Hobart tram network consisted of eight lines, 32 kilometres of track and, at its peak, a fleet size of 75 trams.

You could catch a tram from the city to West Hobart, North Hobart, Lenah Valley, the Cascades, Sandy Bay, Moonah, Glenorchy and Proctors Road. But now you’d never know they were ever here.

So what happened to Hobart’s trams?

That is what Hobart school student and self-described rail enthusiast Harrison Steicke wanted to know, as did plenty of others who voted for the ABC to investigate, as part of Curious Hobart.

Why did they disappear?

Hobart City Council took over the running of the trams from private operators in 1913.

Then in 1955, amid public rancour about fare prices, the State Government wrested control.

By that time electric buses had already replaced trams on some lines, but motorised buses were seen as the future.

Accidents did not help the network’s reputation. After three derailments, all the double-deckers were cut down to single decks.

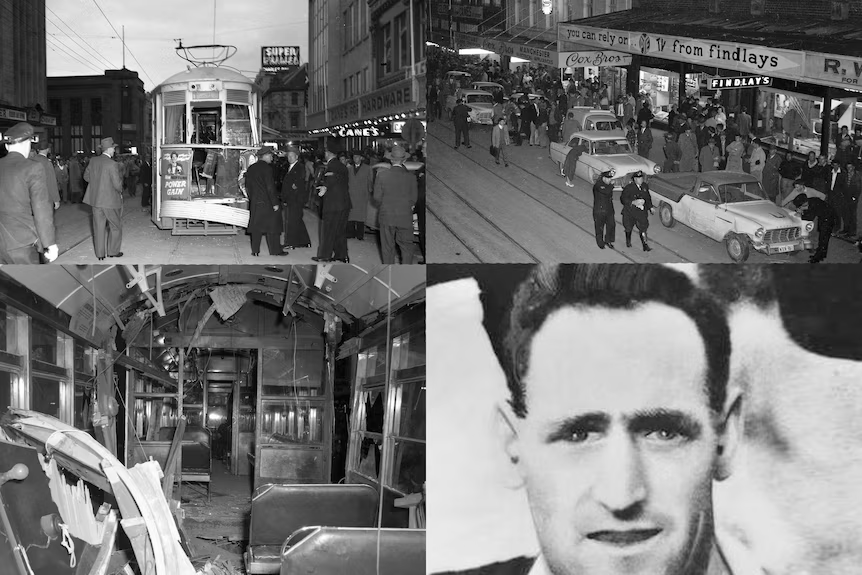

On 29 April 1960, the brakes of a tram on Elizabeth Street failed after a collision and it began rolling backwards down the steep incline towards the city.

As the reversing car gathered speed, conductor Raymond Tasman Donoghue ordered passengers to the front while he moved to the rear.

He tried without success to engage the hand brake and kept ringing the bell to clear traffic and pedestrians out of the way.

The tram crashed into the next tram behind at a speed of up to 80 kilometres per hour.

Mr Donoghue was killed and 47 passengers were injured.

Six months later Mr Donoghue, who had also survived World War II as a prisoner in a German POW camp, was awarded the George Cross — the highest civilian award for bravery.

The demise of Hobart’s tram network soon followed — the last iron car shuttled down the last remaining line (Springfield) the same year Mr Donoghue died.

The trams were sold off for 50 pounds a pop. The wheels and motors of just about all of them were cut down and sold to Japan as scrap metal.

And in the end, only one was left intact — five high schoolboys raised the money to save it and now it resides at the Transport Museum in Glenorchy.

Where did they go?

Other Hobart trams dispersed far and wide, even interstate.

History buff Jeremy Kays sourced two and has spent years trying to restore them.

He keeps Tram #120 — built in 1936 and decommissioned in 1959 — in a shed in an industrial park south of Hobart.

“It ended up as a fishing shack at Interlaken, in the Tasmanian highlands, and it was there for maybe 20 to 25 years,” Mr Kays said.

In the 1980s #120 was taken to Canberra as part of an idea to build a venue out of old trams.

The plan never came to be and Mr Kays brought it home via the Spirit of Tasmania.

Five or six years ago, he bought a second tram, #136, which he said featured at a service station in the northern suburbs of Hobart.

At some point it was cut in half, with one half moved to Eaglehawk Neck.

“There’s probably half a dozen that still exist … that are built into shacks around the state,” Mr Kay said.

He said a lot would have been lost in the 1967 bushfires, or fallen into disrepair.

Three trams restored

The Hobart City Council has also made an effort to preserve history.

The council has five old trams, including one of the unique double-deckers, and Tony Colman has spent eight years bringing three back to life.

“I’ve always had an interest in old things and I went to school on trams,” he said.

“I remember the accident in 1960, so naturally I was interested.”

One of the restored trams is #39, which was bought from a farmer at Oatlands who had turned it into a weekender.

“The first thing I did was get rid of all the things that had been added to the tram,” Mr Colman said.

“It had been turned into a house so it had leadlight windows, a kitchen up one end, the interior was completely stripped to a big degree.

The trams have been restored as close to the original as possible.”

“There’s quite a few trades involved,” Mr Colman said.

“It’s not all woodwork — there’s metal work, and there’s painting, even in the later trams there’s upholstery.

“Apart from having to wire and modernise to allow for better lighting as in indicators and exterior lighting, it’s pretty well exactly as it was.”

Am I ever going to see a tram again?

There is currently a plan before the Hobart City Council to resurrect the city’s trams as a heritage tourist ride running north of the city along the waterfront.

“Our dream is to have a tram museum located near the railway line in Hobart and have them operating between the Regatta Grounds and Cornelian Bay on the disused rail track,” Mr Kays said.

“I think we can probably accomplish that within a couple of years.”

The trams can run on the same gauge as the standard rail tracks which extend out to Brighton and beyond.

“These trams are quite capable and the three that are restored have got new trucks. All the running gear was reproduced in Bendigo, Victoria,” Mr Colman said.

Mr Colman said he was sure the glory days of the Hobart tram will return.

“They will run again.”

ABC News

Trams would be very useful there now as the city has grown. Trams in Bendigo too?

Ballarat not so sure.